Cooling Towers: The Evolution of Scale Control — Part 5

Key Highlights

- Scale formation in cooling systems is primarily driven by calcium carbonate and other mineral deposits, which can impair heat transfer and cause equipment damage.

- Advancements in software tools enable precise calculation of scaling risks and the effectiveness of various chemical inhibitors, improving treatment accuracy.

- Environmental regulations have shifted treatment practices from acid-chromate programs to non-phosphate, polymer-based solutions to reduce ecological impact.

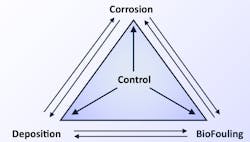

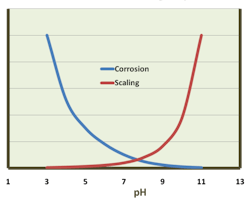

As a refresher, the three major water-related issues that require the most attention in cooling systems are illustrated in the well-known control triangle seen in Figure 1.

Scale-control programs usually are combined with corrosion-control methods, as it is quite possible for both to occur in cooling systems simultaneously.

The Leading Culprit

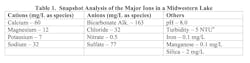

In most water supplies, the leading scale-former is calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Even in seemingly pristine water sources, conditions can make this issue troublesome. Consider Table 1, which provides a snapshot analysis of a lake in the Midwest United States that was built for power plant cooling and recreational purposes. It’s a quite clean water supply without high concentrations of mineral compounds.

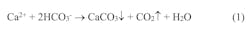

Although this plant has once-through cooling and not cooling towers, similar waters are very common as the supply for many facilities with towers. Part 1 of this series outlined how evaporation in the tower provides most of the heat transfer and that the process increases dissolved and suspended solids concentrations. This means that even at relatively modest cycles of concentration (COC), the levels of all impurities still increase substantially. The solubility of calcium and bicarbonate ions in combination is low, and if the solubility limit is exceeded, the following reaction will occur.

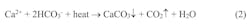

A factor that exacerbates the scaling potential is calcium carbonate’s inverse solubility with temperature. Per this effect, Equation 1 above can be modified to:

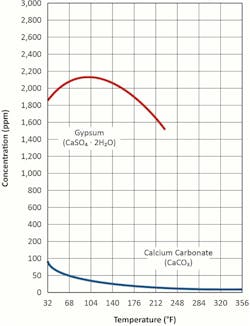

This influence, along with that of gypsum, is illustrated in Figure 2.

An everyday example of this reverse solubility occurs in home plumbing systems, where hot water lines and showerheads accumulate calcium carbonate deposits (often incorrectly termed “lime scale”). The deposition can be very pronounced in industrial heat exchangers.

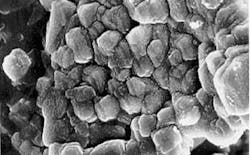

Figure 3 shows calcium carbonate scale in an extracted portion of a steam surface condenser tube.

The Langelier Breakthrough

Many seasoned water-treatment personnel are familiar with the Langelier Saturation Index (LSI), developed by Wilfred Langelier while researching corrosion issues in the water supply piping for the city of Cleveland in the 1930s. He found that corrosion could be reduced by raising the water pH, but that this would increase the calcium carbonate scaling potential. Without delving into the details of the LSI program, his calculations could predict when calcium carbonate scaling would occur from measurements of calcium, bicarbonate alkalinity, pH and total dissolved solids throughout the common water temperature range.

A value of “0” from the program suggested that the water was neither corrosive nor scale forming from a CaCO3 aspect. Movement toward negative values suggest increasingly corrosive conditions, while positive values predict scale formation.

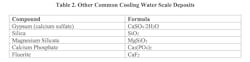

The LSI calculations were subsequently refined by John Ryznar and then Paul Puckorius, but one aspect that all methods had in common was a focus on calcium carbonate scaling. Of course, natural water supplies contain many other dissolved solids that can form deposition products.

Table 2 outlines the most common but by no means all potential scale products.

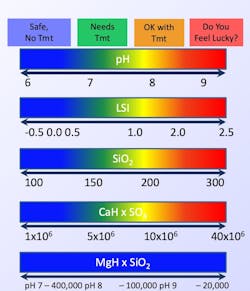

General guidelines for solubility limits for some of the major compounds are shown in Figure 4.

Silica (SiO2) represents unique challenges in waters that contain appreciable quantities. At lower pH, it can precipitate as the straight compound. As pH rises to eight and above, silica will begin to precipitate with magnesium ions (Mg2+) and sometimes other cations. Silica deposits are very insulating and quite difficult to remove.

Computer programs have emerged that can calculate the scaling potential for many species and determine the effectiveness of a variety of scale inhibitors. The most well-known of these is French Creek Software.

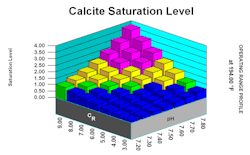

Figure 5 illustrates a display screen for a calcium carbonate scaling scenario.

Accurate water analyses are necessary for proper results. The software integrates this data with other parameters including pH, temperature, COC and ion-ion interactions and then calculates scaling potential over a full spectrum of conditions. The database includes a comprehensive list of treatment chemicals, which the user can select to see what chemical or blend of chemicals is most effective for control of scale-forming constituents. Whenever the user inputs a new parameter, the display will immediately reset to indicate how that parameter influences scaling potential.

Scale Control Through the Years

Consider Equation 1 again. The reaction moves to the left with the addition of acid. Per that chemistry, in the middle of the last century a very popular scale/corrosion control treatment program emerged for open-recirculating (cooling tower-based) systems. It consisted of sulfuric acid feed for scale control (to establish a pH range of around 6.5-7.0 and reduce bicarbonate alkalinity), combined with sodium dichromate (Na2Cr2O7) for corrosion control. The latter compound provides chromate ions (CrO42-) that react with carbon steel to form a protective stainless steel-like surface layer.

Acid-chromate programs were easy to control, but in the 1970s and 1980s, environmental toxicologists began to recognize the dangers of hexavalent chromium (Cr6+). The implications were so severe that they led to a ban on chromium discharge to the environment, which eliminated chromate treatment for open-cooling water systems. The replacement was quite different, with a key concept being operation at a mildly basic pH (typically around 8.0 or perhaps a bit higher) to assist with corrosion control. Inorganic and organic phosphates (aka, phosphonates) became the core treatment chemicals to raise pH and also to generate reaction products that helped inhibit corrosion. But this more complicated chemistry (as compared to acid-chromate) increased scaling potential. Figure 6 illustrates the general relationship between corrosion and scaling.

As phosphate-phosphonate chemistry replaced acid-chromate, calcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2) deposition became problematic in many systems. Formulations evolved, which included polyphosphates, polymers and often a small concentration of zinc — all designed for integrated corrosion and scale control.

While phosphate-phosphonate programs have been around for decades, control is often like operating on the razor’s edge, where variables including water hardness, pH, water temperature, water flow rate, heat exchanger skin temperatures and other factors can move chemistry out of control ranges.

A vivid example of potential problems is shown in Figure 7 of a two-pass tube-and-shell heat exchanger, whose cooling water at the time was treated with a traditional phosphate-phosphonate program.

At the inlet end (the lower half of this heat exchanger), corrosion was problematic. At the warmer outlet side (the top half), deposition was an issue. So, the phosphate treatment program was not particularly effective for either corrosion or scale control.

Another factor influencing scale control programs regards discharge of phosphorus-containing wastewater streams, such as cooling tower blowdown, which has come under increased scrutiny and regulation per the influence of phosphorus on algae blooms in receiving bodies of water. As the following photo shows, algae growth can afflict many water bodies, not just those in warm-weather climates.

The need for more effective chemistry control coupled with tighter environmental regulations led to development of reduced- or non-phosphorus chemistry. Reference 3 discusses pioneering work from experts who formulated a non-phosphate chemistry that “interact[s] directly with metal surfaces to form a reactive polyhydroxy starch inhibitor (RPSI) complex that is independent of calcium, pH or other water chemistry constituents.”

Related Content

Cooling Towers: A Critical but Often Neglected Plant Component – Part 1

Cooling Towers: A Critical but Often Neglected Plant Component – Part 2

Cooling Towers: Corrosion Mechanisms to Critical Failures — Part 3

Cooling Towers: Managing Galvanic Corrosion and White Rust Formation — Part 4

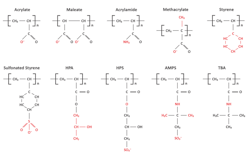

The core compounds establish a stable protective layer on metal surfaces to inhibit corrosion. Regarding scale control for these non-P programs, effective polymeric compounds have emerged. Figure 9 illustrates the active sites on many of the most common polymers.

Scale inhibitors can control deposition through several mechanisms, including sequestration, crystal modification and crystal dispersion. Figures 10a and b illustrate crystal modification, where just a relatively small concentration of polymer can alter crystalline structures such that the deposits do not adhere tightly but wash away.

A key to these (and other) chemistry programs is a thorough chemistry evaluation of the water to be treated with multiple sampling over time. Many cases are known where selection of water treatment programs or water treatment equipment designs has been marred by lack of sufficient water quality data.

Scale Prevention Takeaways

Numerous constituents in the makeup water for cooling and other water systems can, under the influence of numerous factors, form scale deposits that inhibit energy transfer in heat exchangers. Deposits inhibit heat transfer and can induce under-deposit corrosion. Additional details about scale formation and control are available in the handbooks of industrial water treatment firms such as ChemTreat and Ecolab-Nalco.

Disclaimer

This article offers general information and should not serve as a design specification. Every project has unique aspects that must be individually evaluated by experts from reputable water treatment firms. Also, any issues that could potentially have an environmental influence, for example, wastewater discharge from a proposed makeup, process, or cooling water treatment system, must be presented to and approved by the proper environmental regulators during the project design phase.

References

- Post, R., Buecker, B., and Shulder, S., “Power Plant Cooling Water Fundamentals”; pre-workshop seminar for the 37th Annual Electric Utility Chemistry Workshop, June 6-8, 2017, Champaign, Illinois.

- Buecker, B., “Cooling Towers: A Critical but Often Neglected Plant Component – Part 1”; Chemical Processing, September 2024.

- Post, R., and Kalakodimi, P., “The Development and Application of Non-Phosphorus Corrosion Inhibitors for Cooling Water Systems”; presented at the World Energy Congress, Atlanta, Georgia, October 2017.

About the Author

Brad Buecker, SAMCO Technologies, Buecker & Associates, LLC

President, Buecker & Associates, LLC

Brad Buecker currently serves as senior technical consultant with SAMCO Technologies and is the owner of Buecker & Associates, LLC, which provides independent technical writing/marketing services. Buecker has many years of experience in or supporting the power industry, much of it in steam generation chemistry, water treatment, air quality control, and results engineering positions with City Water, Light & Power (Springfield, Illinois) and Kansas City Power & Light Company's (now Evergy) La Cygne, Kansas, station. His work also included 11 years with two engineering firms, Burns & McDonnell and Kiewit, and two years as acting water/wastewater supervisor at a chemical plant. Buecker has a B.S. in chemistry from Iowa State University with additional coursework in fluid mechanics, energy and materials balances, and advanced inorganic chemistry. He has authored or co-authored over 300 articles for various technical trade magazines, and he has written three books on power plant chemistry and air pollution control. He is a member of AMPP, ACS, AIChE, AIST, ASME, AWT, CTI, and he is active with Power-Gen International, the Electric Utility & Cogeneration Chemistry Workshop, and the International Water Conference.