Plant InSites: Why This Water Pump Kept Cycling Off

A retired colleague has taken up a side hobby to keep busy. He’s now on the board of a small municipal water utility and acts as an in-house technical resource for the utility. We often discuss problems that look just like process plant problems but on a smaller scale and with only a tiny budget to fix things.

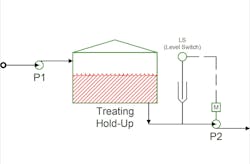

A recent case illustrates using inappropriate instruments to control a process. Figure 1 gives a simplified view of part of the plant. Pump P1 supplies water to a relatively small-volume tank. Pump P2 takes water from the tank and sends it to the water tower. Around the tank, not shown, is a chlorination system for water treating. To prevent a chlorine release it’s important to always keep pump P2 under positive suction seal.

The tank has a roughly 36-minute residence time between the usable high level and the usable low level. Like many small water plants, this facility routinely runs with minimal or no supervision. Part of the flow system has situations where pumps P1 and P2 run for 45 minutes simultaneously. Pumps P1 and P2 have close to the same rate. However, even identical pumps will not have identical flow rates due to manufacturing and maintenance differences. Also, P2 rates vary with downstream pressure (height of water in the water tower). Under some conditions, P2 rates can be substantially higher than P1 rates.

To protect the system, level switches can shut off the P1 and P2 pumps. A low level in the tank switches off P2. Figure 1 illustrates this part of the system. A level switch on a pipe well installed on the P2 suction cuts electricity to the pump motor off. When level rises, the switch trips a relay that turns the pump motor back on. Often, P2 cycles rapidly and eventually the motor control circuit trips P2 permanently to prevent motor damage. At this point, maintenance must come out and reset the pump motor.

By the time the maintenance technician arrives, the level in the tank has risen significantly since P1 is still running. P2 is turned on and seems to work fine. The puzzled tech can’t see anything wrong with the system and moves on to other things. The level gradually drops in the treating tank, and the cycle repeats.

The level switch (LS) acts as an on-off controller with a very narrow dead band. The height of water in the well cannot be directly observed, but the dead band is currently believed to be a few inches.

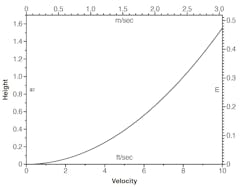

This brings up a second point. Normally a few inches of pressure difference in a system isn’t critical. But with such a narrow dead band we must look at the velocity head in the line. Going back to Bernoulli, reducing velocity causes a rise in static pressure. When P2 turns off, the drop to zero flow rate in the line causes the level in the level well to rise. Figure 2 plots pipe velocity in the inlet line versus equivalent static head change via Bernoulli’s equation.

The normal operating condition is 2.84 ft/sec in the feed line. Figure 2 shows this equivalent to a section head of 1.5 inches of fluid (0.125 ft). As stated, normally a few inches of fluid pressure drop isn’t too critical. Here, the on-off range of the level switch is only a few inches so three inches of velocity head in the inlet is important. By itself, the sudden rise in liquid in the level measurement well due to velocity changes is a major contributor to rapid motor cycling at P2.

As you read this, new level instruments are being installed, and the control system will have a dead-band added to prevent P2 cycling rapidly. Future columns will look at the results of this and explore other elements. This system may be simple, but it gives clear examples we can learn from and apply in understanding our own plants.

Other columns you can check cover inlet velocity in pumping systems and using velocity head calculations.

About the Author

Andrew Sloley, Plant InSites columnist

Contributing Editor

ANDREW SLOLEY is a Chemical Processing Contributing Editor.