Surface Treatment Enhances Condensation

Teaming nanotexturing of a condenser's surface with a lubricant significantly improves heat transfer, report researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, Mass. The team covered a surface with nano-sized posts, or bumps, 10 µm wide and added a coating of lubricant, such as oil (Figure 1). The researchers found that capillary action held the oil between posts in place, allowing droplets of water to condense on the nanotextured surface 10,000× faster than on surfaces using just hydrophobic patterning. The faster velocity boosts condenser performance as it allows droplets to fall from the surface quickly so new ones can form. More details appear in a recent article in the journal ACS Nano.

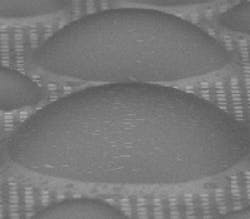

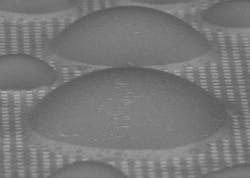

OPTIMIZED CONDENSATION

Lubricated, nanotextured surface treatment allows dome-shaped droplets of water to condense and move quickly across the surface. Source: Varanasi Laboratory, MIT.Kripa Varanasi, the Doherty Associate Professor of Ocean Utilization at MIT, says he's never seen this behavior in more than a decade of work on hydrophobic surfaces. "These are just crazy velocities." The posts securely pin the lubricant in place to form a thin coating, so the amount of lubricant needed is minimal. A small reservoir at the edge of the surface replaces any lost lubricant. Varanasi notes that the lubricant can be designed to have such low vapor pressure that "you can even put it in a vacuum, and it won't evaporate."Manufacturing the system is easy, adds Varanasi. The surface texture can be configured in any pattern as long as the dimensions are right.Once textured, the surface can be dipped in lubricant and pulled out. Most of the lubricant simply drains off, and "only the liquid in the cavities is held in by capillary forces," says MIT postdoc Sushant Anand, who also worked on the project. Because the coating is so thin, it only takes about a ¼ - to a ½-teaspoon of lubricant to coat a square yard of the material, he adds. The lubricant also can protect the underlying metal surface from corrosion.The next step is to research and quantify exactly how much improvement the new technique can provide in power plants where steam-powered turbines are common. "Even if it saves 1%, that's huge" in its potential impact on greenhouse gas emissions, exclaims Varanasi.The new approach works with a variety of surface textures and lubricants; ongoing research will focus on finding optimal combinations for cost and durability. "There's a lot of science in how you design these liquids and textures," Varanasi says.