Wastewater Yields Fertilizer

Operators of sewage treatment and food processing plants as well as biogas facilities may gain a profitable sideline by producing high-quality slow-release phosphate fertilizers from their wastewaters, say researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB, Stuttgart, Germany. They have developed a process that precipitates struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) as tiny crystals suitable for direct application as fertilizer while reducing phosphorus to levels that comply with wastewater-discharge regulations.

[sidebar id="ID"]

Currently, wastewater treatment plants typically remove phosphate by precipitation with aluminum or iron salts to form aluminum and iron phosphate, which can't be used as fertilizers, notes Fraunhofer. This results in a loss of about 4.3 million metric tons of phosphorus worldwide each year.

Fraunhofer's patented approach doesn't require adding salts or bases. "It is an entirely chemical-free process," notes Jennifer Bilbao, who led the development team. The method can lower phosphorus concentration in wastewater by 99.7%, to less than 2 mg/L. It suits streams rich in ammonium and phosphates and without contaminants like heavy metals.

The process relies on an electrolytic cell with an inert cathode and a sacrificial magnesium anode. Oxidation at the anode releases into the wastewater solution magnesium ions that then react with phosphate and ammonium molecules to form struvite.

"With all wastewaters tested at the moment we measured a maximum energy consumption of 70 Wh/m3. This is the energy required for the electrolytic process, which is ten times lower than the energy required for pumping the wastewater. Hence, we can say that the energy consumption for the electrolytic process is negligible. The [higher] the ion concentration is, the [lower] will be the energy consumption," explains Bilbao.

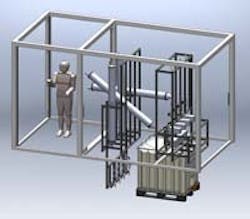

The researchers have built a mobile pilot plant (Figure 1) with a 2-m-high electrolysis cell that handles a volume flow of 1 m3 of wastewater per hour. It had been running at Fraunhoffer's site, using sludge supernatant from anaerobic fermentation of activated sludge from a municipal wastewater treatment plant, but now has been moved to a biogas plant.

"We intend to spend the next few months testing the mobile pilot plant at a variety of plants before starting to commercialize the process in collaboration with industrial partners [Bamo IER, E.R.S. and Geltz Umwelttechnologie] early next year," she says. The plan is to offer plants first in Europe and then in North America.