Optimize Reactive Crystallization

Fine chemical and pharmaceutical companies often employ reactive crystallization or precipitation to make intermediates and finished products. It is perhaps best to think of precipitation as embodying fast crystallization in which the particles can be either amorphous, crystalline or a combination of the two. The reactions can be very fast compared to the mass transfer rates to the crystals and their growth rates, often leading to high local supersaturations and extensive nucleation. In some cases, due to high supersaturation, the crystals or precipitates are small, in the submicron to several micron range. Such small particles usually are undesirable because they can present problems in downstream operations such as filtration, washing and drying. Agglomeration of some of the individual crystallites frequently occurs — but doesn't remove all small particles.

This is not to imply that precipitations always result in agglomerates. Many cases exist in which the particles are single crystals with different degrees of faceting.

As with any crystallization, the balance between nucleation and growth determines the size distribution. The high level of supersaturation may result in high nucleation rates and a smaller size distribution. Inclusion of solvent and trapping of impurities also can occur. In addition, other physical properties such as bulk density, caking and a small size, broad or bimodal distribution can pose difficulties for storage and formulation.

CONTROL OF CRYSTAL SIZE

For compounds with high kinetic rates, reduced concentration and elevated temperatures often help in making a larger particle. The rate of addition of reactants enables control of supersaturation globally but not locally should the reaction occur at the feed point. Therefore, a careful balance among the reactant addition rate, local and global supersaturation, mass transfer and crystal surface area is crucial. For entities with slow crystallization kinetics, the rate of addition of reactants alone can provide an effective method of supersaturation control. Raising the operating temperature, even by a small amount, decreases the supersaturation due to the increasing solubility versus temperature of most compounds. It's important to generate the solubility curve to determine the operating parameters that facilitate the production of a larger particle, if that's the goal.

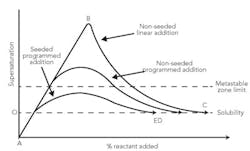

Figure 1 shows three potential modes for reactive crystallization. The figure illustrates three reactant addition methodologies: linear (A, B, C), programmed (A, D) and programmed with seeding (A, E). Programmed addition with seeding is preferred if larger crystals are required. The first quantity of reactant added usually creates a high local supersaturation value. Thus, it's desirable to stay within the metastable zone by control of the addition rate and seeding.

KEY PARAMETERS

Many organic bases and acids are prepared by reactive crystallization that can lead to high supersaturation with potential high nucleation. The same occurs for inorganic precipitations. A common method is to add a reactant to a solution with dissolved second reactant to produce the product. Rate processes that can impact results include:

• chemical reaction to make the product;

• formation of clusters in solution that then exceed the solubility and create nuclei;

• production of the insoluble phase either as an amorphous solid and oil or a crystalline solid;

• simultaneous production of supersaturation with reactant addition along with its consumption by nucleation and growth;

• impact of impurities or deliberate dosing of additives on nucleation and growth;

• secondary effects including agglomeration, crystal breakage, ripening and polymorphs;

• impact of mixing including meso- and macromixing during addition to ensure molecular-scale contact and reaction along with meso- and micromixing for molecular-scale homogeneity; and

• effect of operating temperature on solubility and supersaturation and resultant kinetics.

MIXING PARAMETERS

Three modes of mixing — macromixing, mesomixing and micromixing — may affect the resultant product.

Macromixing involves the bulk blending in the vessel. Compounds with long nucleation induction times or slow reaction rates may not form crystals in the micromixing or mesomixing zones but will do so in the bulk blending phase of the overall mixing process.

Mesomixing effects occur in agitated vessels when the reactant feed rate is faster than the local mixing rate, yielding a plume of reactant concentration that's not mixed at the molecular level. This parameter is significant on scaleup and often results in the need for longer addition times in a larger vessel to achieve the same reaction selectivity and particle-size distribution.

Micromixing is key because the time for blending at the molecular level is critical for both the chemical reaction and nucleation induction time and, thus, for determining the nucleation rate and size distribution. The location of the reactant feed pipe, impeller speed, and impeller type and baffling affect the micromixing times. These vary by a large factor at different locations in the vessel and also depending upon agitator speed and design.

A critical factor in both micro- and mesomixing times is the feed pipe location. A change in the size distribution at modified feed pipe locations indicates a mixing dependence. If no substantial variations exist, a different system property such as nucleation induction time may be slow compared to micromixing. If the reaction is slow, it may occur in the bulk mixing volumes of the vessel.

Organic species, in particular, demonstrate a wide range of nucleation induction times. The faster times are on the order of milliseconds, which is comparable to micromixing times in agitated vessels. In this case, agitation will significantly impact particle formation. The addition of reactant feed into poorly mixed volumes in the vessel can extend micromixing and mesomixing times by up to several orders of magnitude, thereby making mixing more important even with longer nucleation induction times. Particle formation is even more complex when the reaction times bracket these time frames.

To minimize nucleation while maximizing growth, it's important to achieve micromixing of the two reactants faster than the nucleation induction and reaction times, while also providing adequate meso- and macromixing to create a controlled rate of supersaturation generation. Seed surface area and controlled mass transfer to the growing crystals can encourage growth. However, excessive mixing can decrease the induction time, thereby increasing nucleation as well as crystal breakage and secondary nucleation. This underlines the importance of appropriate agitator design and power input.

NUCLEATION INDUCTION TIME

This is critical due to its relationship to reaction and mixing time. At the feed point, mixing, reaction and nucleation may be occurring within the same time frame in series or in parallel depending upon the time constants. If they happen in parallel, agitation at the molecular level may not be completed before the initiation of reaction. If the induction time is also short, inclusion of unreacted substrate in the nucleation mass at high supersaturation is possible. In this case, the times for mixing (Tmix), reaction (Tr) and induction (Tind) are approximately equal:

Tmix ~ Tr ~ Tind

Ideally, the mixing at a local level should be adequate to achieve reactant blending at the molecular level before reaction, and the reaction is completed in less than Tind and yields nuclei of the desired molecular composition. In this case:

Tmix < Tr < Tind

Agitator and speed selection can alter mixing time. However, Tr and Tind are system specific — with both being concentration dependent and Tind also being a function of supersaturation.

SUPERSATURATION

Control of local and global supersaturation, while required, is difficult at the feed point due to the low solubility of many compounds produced by reaction. Supersaturation can be reduced by mixing, as well as by a number of other parameters:

• reactant addition time — to maintain global supersaturation in the metastable zone;

• seed/crystal surface area — to decrease nucleation at the beginning of reactant addition, thereby preventing excessive nucleation that could limit growth of particles;

• the balance between addition rate and crystal surface area available for growth — maintaining an appropriate balance can avoid additional nucleation and a bimodal size distribution; and

• determining the impact of operating temperature on the particle-size distribution — higher temperatures often are beneficial as long as chemical degradation doesn't occur; cooling following the initial precipitation reaction then increases the yield based on the solubility curve.

SECONDARY EFFECTS

Reactive crystallizations, due to the high local supersaturations, are subject to oiling out or agglomeration. The low solubility can cause a second liquid phase to form. The oil then can solidify into an amorphous solid or crystalline form. If this happens, agglomeration frequently occurs as a result of the adhesive oily phase holding particles together. Agglomeration yielding large structures of individual crystallites or amorphous solids can entrap impurities, reactants and solvents. At times, these structures have enough strength to survive filtration, washing and drying. At other times, the agglomerates are quite weak and disintegrate during mixing, pumping, filtration and drying.

The most effective approach for preventing oiling out and agglomeration is to ensure low supersaturation within the metastable zone, thereby supporting growth while minimizing nucleation. Excellent agitation, seeding and slow reactant addition can achieve that.

Nucleation rate dictates the final size distribution; if nucleation continues during the reactant addition, the mean crystal size can be small, perhaps a few microns, and broad with a potential bimodal distribution resulting from additional nuclei formation and the growth of existing crystals.

SEEDING

Seeding is an important parameter to avoid excessive nucleation and reduction in particle size. If the system is of low growth rate, seeding won't help as much. Keep in mind:

• The amount, size, surface area and surface properties of the seeds are critical.

• The seed amount should be at least 10–20% of the final crystal mass.

• The recommended seed size in most cases is approximately one-third to one-half of the desired final-product size.

• Seed should be added as a slurry or as a heel from the previous batch. Dry addition and milled seeds often don't work as well.

GROWTH CONSIDERATIONS

Often the inherent growth rate of organic compounds is slow, requiring reactant addition over extended periods to maintain supersaturation within the metastable zone. Higher addition rates can result in excessive nucleation and a bimodal distribution. Experiments in which the feed rate is increased while other parameters are held constant can determine the allowable addition rate. A number of programmed addition strategies have been proposed. One keeps the initial feed concentration low and then increases it as the reactant addition proceeds. This is similar to programmed cooling or programmed addition rate of antisolvent.

MIXING SIMULATIONS

A number of software programs can handle the analysis and scaleup of mixing systems for crystallization and precipitations. One I've successfully employed is Visimix.

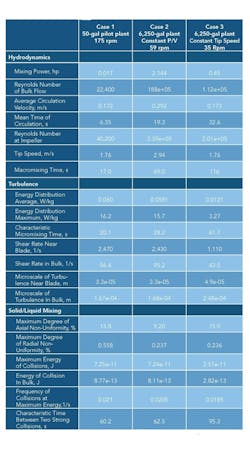

Such a program enables investigating different scenarios for scaleup as well as changes in agitator and vessel configuration. Table 1 presents the Visimix output for a geometric scaleup of a reaction crystallization from 50 gal to 6,250 gal, the first with constant power input to volume (P/V) and the second with constant tip speed. The vessels were baffled, with a dished head and a four-blade 45° pitched blade turbine. At completion there were 15% suspended solids in a saturated aqueous mother liquor and an average particle size of 150 microns with a maximum size of 250 microns. The slurry viscosity was 3 cP with a slurry density of 70 lb/ft3. The simulations clearly show the dramatic difference in hydrodynamic and turbulent values on scaleup and the impact of holding a particular parameter constant.

The software allows you to vary reactant concentration and feed position, thereby comparing the reaction time to the mixing time. The important issues to know are the energy of dissipation at the feed location and the direction of flow in this zone, both of which can be calculated by Visimix.

A better method for scaleup might be the use of different geometries and types of agitators for the pilot unit versus the commercial plant.

WAYNE J. GENCK is principal of Genck International, Park Forest, Ill. He answers crystallization questions on CP's Ask the Experts forum. E-mail him at [email protected].