Washington targets plant security

As you’re reading this article, Congress passed or didn’t pass comprehensive chemical security legislation — or Congress did or didn’t include in the appropriations bill for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) direction for DHS to promulgate security regulations for critical chemical facilities. As we are writing this, members of Congress and others are calling for DHS and Capitol Hill to move quickly to impose at least minimum security requirements on such facilities. Nevertheless, we don’t know at this point whether federal chemical security legislation will happen in 2006.

Some states have moved ahead in advance of federal action. In 2002, Baltimore enacted a city ordinance followed by Maryland legislation in 2004 that requires chemical facilities to conduct security vulnerability assessments and implement security measures commensurate with the finding of the assessments. Also in 2004 New York enacted legislation directing the State Office of Homeland Security to first identify and then assess security at critical chemical facilities in the state. In November 2005, New Jersey’s governor signed an order mandating security standards, including consideration of inherently safer technology, for certain chemical facilities. The sidebar highlights these requirements.

Significant public risk

|

New Jersey Domestic Security Preparedness Task Force Order mandating security standards for TCPA/DPCC chemical facilities Applies to 140 N.J. chemical facilities, including 43 subject to the State’s Toxic Catastrophe Prevention Act (TCPA) program. All facilities must:

Security assessments must include a critical review of:

TCPA facilities must also analyze and report the feasibility of:

|

Some security pundits believe that chemical facilities in populated areas pose risks comparable to those of commercial nuclear power plants or even weapons of mass destruction. During a February 2004 hearing on security vulnerabilities at chemical plants, representatives from the Government Accountability Office testified that “experts agree that the nation’s chemical facilities may be attractive targets for terrorists intent on causing massive damage.” Even the American Chemistry Council has called on Congress to give the DHS authority to require vulnerability assessments and security plans at critical chemical facilities and to enforce those requirements.

Despite this concern, comprehensive federal chemical security legislation has been actively debated in both houses of Congress this year. The Senate Homeland Security Committee passed S. 2145, the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Act, in June and placed it on the Senate legislative calendar to await floor debate. The House Homeland Security Committee passed a different Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Act, H.R. 5695, in August and referred it to the Energy and Commerce Committee. In the meantime, the Senate accepted a provision to the 2007 DHS appropriations bill that would direct DHS to promulgate chemical facility regulations within six months.

While Congress has considered chemical facility security legislation every session since 2002, actions have been stymied over both substantive and jurisdictional disagreements: which committees in each house have sole or shared jurisdiction for the issue, whether EPA or DHS should have the regulatory authority, whether federal law should pre-empt state and local measures, whether facilities regulated under the Marine Transportation Security Act (MTSA) should be “grandfathered” in any new regulatory program, and whether high priority chemical facilities should be required to consider “inherently safer technologies” (ISTs) as part of their security assessments.

No lack of action

Even without comprehensive chemical security legislation, Congress, DHS and the industry have taken steps to increase security at some chemical facilities. The MTSA, passed in 2002, gave the Coast Guard (now part of DHS) authority over security in the nation’s ports, including vessels, facilities within the port areas and offshore structures. The Coast Guard promulgated regulations for certain facilities — including many chemical ones — that required vulnerability assessments, security measures and security planning to be enforced by the Coast Guard.

In the absence of regulatory authority, DHS has implemented voluntary programs to identify critical chemical sector assets and provide security assessment resources and tools:

- The National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) describes a coordinated, comprehensive risk management framework to establish national homeland security priorities, goals, and requirements for infrastructure protection (per requirements of the Homeland Security Act). As the “Federal Sector-Specific Agency” responsible for chemical sector security, DHS also has written a chemical sector annex to the NIPP.

- Through the Buffer Zone Protection Program (BZPP), DHS works with local high-priority sites and the surrounding law enforcement and emergency responders to develop a plan that will extend a zone of protection out from the facility fence and into the community, to thwart terrorists through measures such as increased law enforcement presence and surveillance. In 2005, DHS announced availability of $91.3 million for state and local officials to purchase equipment to protect community assets.

- DHS has partnered with representatives of the chemical sector to develop a methodology to identify and assess critical chemical facilities based on potential for uncontrolled chemical releases, theft of materials, essentiality of specific products, or economic criticality. This methodology, known as Risk Analysis and Management for Critical Asset Protection (RAMCAP), is based on security assessments developed by the chemical and petroleum industries but enhanced to meet DHS data needs and has been completed for chemical manufacturing, refining, LNG storage, nuclear commercial power and nuclear spent-fuel storage facilities. DHS is developing RAMCAP tools for other critical infrastructure sectors for national cross-sector risk assessment and so owners/operators can estimate potential consequences and vulnerability to an attack using a consistent system of measurements.

- RAMCAP is being used as part of regional Chemical Comprehensive Reviews (CCRs) being piloted to expand the BZPP concept. The first pilot, in Detroit, took place in February, the second and third pilots are expected to be conducted in Chicago and Los Angeles before the end of the year, and three more are planned in 2007. Results of the CCRs are also used to identify regional prevention, response and mitigation needs to respond to attacks at chemical facilities or other critical infrastructure assets in the region.

The chemical industry itself has taken voluntary steps to increase security. The Responsible Care Security Code of the American Chemistry Council (ACC) obligates its members to implement a security management program for facility, value chain and cyber security. The Synthetic Organic Chemical Manufacturers Association (SOCMA) incorporated security into its Chem Stewards program, as did the National Paint and Coatings Association with Coatings Care, and the National Association of Chemical Distributors (NACD) with Responsible Distribution Process. Such programs include requirements to assess security vulnerabilities, implement enhanced security measures to address vulnerabilities, and develop security-management plans. In addition, commercial initiatives are tackling some of the areas of concern, such as better and more-transparent communication among plant systems for security and process control.

What’s likely

Regardless of whether chemical security legislation passes this year, common elements in the DHS plan for the chemical sector and the legislative proposals give a clear indication of what the chemical industry can expect in the coming year. Other aspects are likely to remain under debate.

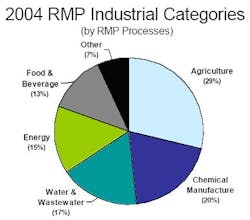

Universe of regulated facilities. Both S. 2145 and H.R. 5695 and DHS’s independent efforts start with sites covered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Risk Management Plan (RMP), 40 CFR Part 68. This list includes more than 14,500 stationary sources, some of which pose questionable homeland security threats or consequences. However, chemical manufacturing makes up only about 20% of RMP regulated processes. The rest are agriculture (29%), water and wastewater treatment (17%), energy (15%) and food and beverage (13%) sites (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Five-step methodology begins with asset characterization and finishes with countermeasure analysis.

This RMP list would have to be rationalized, with the DHS secretary setting criteria for designating a facility as a “chemical source” based on risk. Other chemical sources, such as those supplying critical government facilities or dealing with chemicals not covered by the RMP rule, could be added.

Vulnerability assessments. Both bills also require facilities to conduct vulnerability assessments. Assessment methodologies used in the chemical and petrochemical industry — including those developed by Sandia National Laboratories, AIChE’s Center for Chemical Process Safety, and the American Petroleum Institute/National Petrochemical and Refiners Association, and RAMCAP — describe a similar, multi-step process: 1) identification of critical assets within the facility; 2) analysis of threats to the facility and assets; 3) analysis of consequences of a successful attack; 4) analysis of critical asset vulnerability to attack; 5) assessment of likelihood that an attack against an asset would be successful.

Security measures. S. 245 and H.R. 5695 require chemical sources to conduct vulnerability assessments, implement appropriate security measures, and develop security management plans. Key to the regulations will be the definition of what constitutes a “security measure.”

The bills, DHS, MTSA and the industry agree that minimum security measures would include elements, such as:

- access control for persons, vehicles and shipments;

- perimeter security, including fences, gates and locks;

- technical security equipment, like security lighting, closed circuit cameras and motion detectors; and

- personnel security, including background checks for new hires, contractors and those who transport hazardous materials.

Security plans. There also is general agreement on some elements of security plans, including:

- actions to be taken at elevated threat levels;

- procedures for reporting suspicious incidences or behaviors;

- coordination of security response plans with local law enforcement and federal and state authorities;

- security awareness training; and

- regular security exercises and drills.

Inside the plant gates

Both the voluntary and state programs recognize that chemical facility security requires a multiple “layers of protection” approach made up of both enhanced perimeter security and additional measures between the perimeter and the most critical assets — such as control rooms or critical processing units. The security measures identified as a result of the vulnerability assessments should function as a security system to “deter, detect, delay and mitigate” an attack. The New Jersey mandate goes beyond this security model of protecting and defending critical assets by actually questioning the assets themselves — including the storage and processing of hazardous materials, analysis of the feasibility of alternative materials or operating conditions and of redesign of equipment and processes to minimize equipment failure and human error.

At this point, the shape of federal actions to address such aspects remains unclear. There is widespread agreement on most elements of a chemical security regulatory structure — facility prioritization to identify the most critical facility, vulnerability assessments of the critical assets within a facility, security measures to address identified vulnerabilities, security management plans to maintain a system to deter, detect, delay, and mitigate against attack. However, no agreement exists around the most contentious issue — the role of inherent safety and particularly IST in chemical security (“Inherently Safer Chemical Processes — A Life Cycle Approach,” published in 1996 by the Center for Chemical Process Safety, describes in detail the concept of IST).

Inherent safety and chemical security

The chemical industry has embraced the concept of inherent safety as a step-change approach to either eliminating or significantly mitigating hazards. In some ways, inherent safety can be looked upon as the “pollution prevention” of process safety. That is, it’s more of a philosophy and approach for seeing opportunities than a discrete action or end point. In the same way that federal and state regulatory agencies have opted for programs to encourage rather than mandate pollution prevention, OSHA and EPA have rejected suggestions to mandate inherent safety or IST — instead favoring incentives for developing and sharing of innovative and creative approaches to inherent safety. The agencies recognize that inherent safety is most easily incorporated during the design or re-engineering of a process rather than as a measure added to an existing process.

The Senate bill, S. 2145, contains no explicit requirement to implement IST but does define “security measures” to include “the implementation of measures and controls to prevent, protect against, or reduce the consequences of a terrorist incident, including… the relocation, hardening of the storage or containment, modification, processing, substitution, or reduction of substances of concern.”

The House Homeland Security Committee bill, H.R. 5695, includes both the Senate language and the following:

(a) METHOD TO REDUCE THE CONSEQUENCES OF A TERRORIST ATTACK. — For purposes of this section, the term ‘method to reduce the consequences of a terrorist attack’ includes —

- input substitution;

- catalyst or carrier substitution;

- process redesign (including reuse or recycling of a substance of concern);

- product reformulation;

- procedure simplification;

- technology modification;

- use of less hazardous substances or benign substances;

- use of smaller quantities of substances of concern;

- reduction of hazardous pressures or temperatures;

- reduction of the possibility and potential consequences of equipment failure and human error;

- improvement of inventory control and chemical use efficiency; and

- reduction or elimination of the storage, transportation, handling, disposal, and discharge of substances of concern.

(b) ASSESSMENT REQUIRED. —

- IN GENERAL. — The owner or operator of a facility assigned to the high-risk tier under section 1802(c)(4) shall conduct an assessment of methods to reduce the consequences of a terrorist attack on that chemical facility.”

The term “inherently safer technology” does not explicitly appear, but IST underlies many of the points. Regulations implementing such requirements would have sweeping applicability and significant implications for design and operation of plants handling hazardous materials, especially facilities with EPA Risk Management Planning regulated sources (40 CFR Part 68), which may not pose significant risks or appeal to terrorists.

The anticipated regulatory benefit seems to be that IST can remove hazards entirely or reduce them to de minimis levels and so eliminate the attraction to potential attackers.

These existing and proposed regulations typically end in a goal of IST consideration “to the extent practicable” and sometimes allow cost or feasibility as a basis for justifying whether a change is practicable. There is no standard measurement of what “practicable” means. While companies may believe they are moving toward inherently safer processes, they often find obstacles to the theoretically possible complete application of the four IST strategies.

Issues with IST

The strategies are best implemented early in the process design stage; many companies have already instituted IST concepts in their process designs, particularly where there were additional benefits beyond safety, such as minimizing equipment or inventory. Unfortunately, opportunities to implement IST in existing chemical processes are practically limited to relatively minor changes that only reduce risk incrementally. In many cases, IST options that were relatively easy and cost-effective to take up (such as replacing chlorine with sodium hypochlorite for water treatment) have already been adopted.

The role of IST in chemical process security is currently being debated at a high level in both government and industry. Some proponents clearly see IST as the panacea to security concerns. Unfortunately, IST is sometimes presented as a relatively obvious and simple approach to execute or regulate while the more traditional and proven “deter, detect, delay, mitigate” strategies are disparaged as less effective or reliable.

The inclusion of IST in national chemical security legislation, such as the House bill, presents a dilemma for the chemical industry. While it is generally accepted that IST has the potential to reduce both accidental and intentional process safety hazards, implementation — and especially regulation — of IST generally is generally neither straightforward or easily measured.

There is limited feasibility to implement IST in existing facilities due to costs and other tradeoffs. Industry recognizes that IST is not a “silver bullet” to eliminate security risks and indeed frequently poses tradeoffs that can simply change (or even boost) the danger (e.g., use of smaller shipping containers may reduce the consequences of a container leak but will generally increase the risk associated with transportation and connecting/disconnecting the container from the process). At times “inherent safety” may conflict with environmental goals — inherently hazardous ammonia replaced non-toxic CFC’s in refrigeration systems. Cost also is usually a factor; the application and management of process safeguards (active, passive and procedural) for existing processes often provides an adequate and more-cost-effective level of protection.

Of course, conducting an IST review of an existing process is a worthwhile exercise to identify potential improvements that can reduce the risk associated with accidental and intentional releases, just as conducting a Process Hazards Analysis (PHA) can identify and thus lead to a decrease in the accident risk associated with process hazards. However, as with PHAs, evaluations require the sound judgment of engineering, operational, and other specialists to make informed decisions regarding safety and feasibility.

IST concepts are worthwhile as engineering design guides and as a general philosophy for designing, constructing, maintaining and operating chemical facilities. The concern of industry is that IST alternatives, once identified, will be mandated regardless of feasibility — potentially causing economic or even safety consequences to the facility or to the transportation system. As with process safety/risk management regulations (or any regulation, for that matter), the way that an IST requirement is enforced is the key to the success of such an initiative. Based on the experience in New Jersey, however, it is unlikely that requirements for conducting IST reviews and implementing such technology “where practicable” will result in large-scale risk reduction against security related risks. Exceptions exist, such as the widespread replacement of chlorine use in potable water treatment systems with sodium hypochlorite (“bleach”). However, as with other IST options, risk is not completely eliminated, as the manufacture of the bleach requires the transportation and use of chlorine, which will increase, so in effect the risk is to some extent relocated, not eliminated. As long as these ecosystem-related consequences are identified, better judgments can be made related to the implementation of IST.

A requirement to consider IST is much more problematic. One company spent nearly as much time focusing on inherent safety as it did on its entire security vulnerability assessment. Any national legislation involving IST will almost certainly impose inordinate time demands.

Putting security into focus

New legislative requirement or not — sites that manufacture, use or store hazardous chemicals will be under continued pressure to take measures to increase security. “Critical” facilities will be expected to conduct vulnerability assessments, implement security measures to address the vulnerabilities, and develop security management plans. In the absence of new regulatory authority, DHS will work through chemical sector partners to implement such measure on a voluntary basis. A new chemical security law will give DHS authority to compel such actions.

Security assessment and planning will be demanding, particularly for companies and facilities that have not already taken such steps. Any requirement for IST evaluations and implementation may be especially challenging.

Efforts focused on inherent safety may identify some good risk-reduction opportunities, particularly at sites that have not previously embraced the concept. However, in practice, the approach can’t substantially reduce overall security risk because cost and other factors limit the opportunities for making step changes in the type and quantity of hazardous materials in existing facilities. This is especially true where facilities manufacture a hazardous material or use such materials as feedstocks or catalysts and there are few or no alternatives. Major improvements will generally require substantial investments to modify processes using alternative chemistries or to cut inventories, for example, by constructing a unit onsite to generate only enough of the hazardous materials needed for immediate consumption. In some cases this may be feasible but in most cases it will not. As with process safety, it should be left to the judgment and expertise of knowledgeable company personnel to determine whether IST implementation makes sense for their facility.

The prospect of chemical security regulations is very significant and yet, the outlook still isn’t perfectly clear on the final shape and timing of any requirements. They could potentially create a federal mandate on security of the chemical industry, incorporate the need to evaluate inherent safety more widely than any other regulation in the U.S., and force industry to prove compliance to security “standards.” The challenge for DHS and all those who participate in the regulatory development process will be to make such rules rational, measured, cost-effective and fully justified.

David A. Moore, P.E., C.S.P., is president and C.E.O. of the AcuTech Consulting Group, Alexandria, Va. E-mail him at [email protected]. Dorothy Kellogg, M.P.A., is a senior consultant with the AcuTech Consulting Group in Alexandria, Va. E-mail her at [email protected].