Resins Process Promises Plenty of Pluses

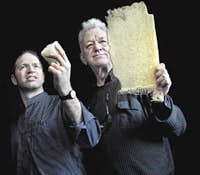

Dutch researchers have used feedstocks derived from biomass to make thermoset materials ranging from rigid foams to flexible sheets. These materials, in contrast to today's petrochemical-based thermosets, are fully biodegradable and non-toxic and don't release any harmful substances upon combustion, say Prof. Gadi Rothenberg and Dr. Albert Alberts (Figure 1) of the Heterogeneous Catalysis and Sustainable Chemistry research group at the University of Amsterdam. Moreover, the straightforward process and renewable-resource-based feedstocks promise plastics that are significantly less expensive than those produced conventionally from petrochemicals, they add.

The process not only is straightforward but doesn't require a catalyst, although one can be used. "We have achieved very high yields. Quantitative yields are possible," notes Rothenberg. "The operating conditions are similar to those used in the resins industry."

The researchers now are evaluating how the resins' physical and mechanical properties and processability compare to conventional products. They expect to have results shortly. "We must provide the same performance or better at the same cost or, preferably, lower," says Rothenberg. "Right now, it looks like our materials will be considerably cheaper."

The new resins potentially could replace polyurethane and polystyrene in construction and packaging applications and epoxies in the production of plywood and medium-density fiberboard.

Process development work is underway -- scaling up the five main product types to the kilogram level. The key challenge, he says, is: "proving to ourselves and others that we can make kilos of this material at a cost that is substantially lower than the competing petroleum-based plastics."

If all goes well, piloting might start in as soon as 12 to 18 months. Already more than 25 companies have expressed interest in cooperating on the development, he notes.

The researchers don't yet know whether producing the resins on an industrial scale will pose any particular obstacles. "But we do not see any crucial process engineering problems," says Rothenberg. The technology most likely will be ready for commercialization in four years, he adds.

He also relates that the development teaches a broader lesson. Experienced plastics people told the researchers: No self-respecting polymer scientist would ever try this out because it is known that doing something like this is stupid and only leads to trouble -- but you did not know this and so you tried and apparently it works. So, he counsels: "Go and try those crazy ideas, and long live the Friday afternoon experiments!"