"Teamwork matters. Teamwork saves lives." That’s the battle cry from Eduardo Salas, the Allyn R. and Gladys M. Cline chair professor in Rice University’s psychological sciences department, and Scott Tannenbaum, president at The Group for Organizational Effectiveness Inc.

Salas and Tannenbaum have been studying team performance for 40 years, with particular focus on high-stakes industries where failures can be catastrophic. Their research has taken on new urgency following incidents like the 2024 Pemex Deer Park refinery tragedy, where a breakdown in team coordination led to two deaths and dozens of injuries. They co-wrote the book "Teams That Work," which outlines the drivers of team effectiveness.

They note that teamwork isn’t as simple as it seems. According to Salas — a human factors, industrial and organizational psychologist — organizations don't know about the science of teamwork. And they don't think they need to know because they think they're executing teamwork.

“I've been to many places where they say, ‘Oh, we're doing team training.’ And when I go in there, they're not really following the science,” says Salas. “They think because they have one course called ‘Teams’ or ‘Teamwork,’ that they are covering the teams concept.”

What is Teamwork?

Salas and Tannenbaum partnered with the Center for Operator Performance (COP) to survey over 400 operators, supervisors and trainers in the petrochemical industry to understand teaming requirements, risks and behaviors. COP is a group of industry, vendor and academia representatives who address human capabilities and limitations through research, collaboration and human factors engineering.

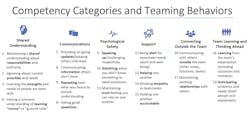

The survey identified 19 different behaviors that enable people to work together well. They placed those 19 characteristics into six competency categories: shared understanding, communications, psychological safety, support, connecting outside the team, and team learning and thinking ahead (Figure 1).

Teamwork is not simply maintaining pleasant interpersonal relationships or occasional social interactions. It represents a sophisticated interplay of skills, communication strategies and collaborative behaviors. It’s about creating robust communication channels where team members can seamlessly exchange critical technical information, acknowledge knowledge gaps and collectively solve complex problems.

Salas notes there is a distinction between dynamic teaming and traditional teamwork. “In more traditional teamwork, you're working with the same people, doing pretty similar tasks,” he says. “But what we found in the COP work is that there's as much or more dynamic teaming occurring where I may be dealing with a different maintenance person yesterday than today, I might be focused in on my group of console operators for this one thing and then it hops over to something else. So, it's this dynamic membership and dynamic tasking that makes it more challenging.”

The Deadly Sins of Bad Teamwork

- Ego-Driven Silence: When team members are too proud to admit they don't know something.

- Communication Silos: Treating other departments like they're a separate company altogether.

- Reactive Instead of Proactive: Only addressing team issues after something goes wrong.

- Superficial Training: Thinking a one-hour workshop makes you a team player.

Tannenbaum adds that while technical knowledge forms the foundation of professional excellence, the ability to work effectively as a team has become increasingly crucial in terms of success and survival.

“One of the interesting things from the Center for Operator Performance work that we did is that when we got information from operators and maintenance folks, they reported that about three-quarters of their work involves communicating and coordinating,” says Tannenbaum. “You think about that as both an opportunity and a risk point.”

Illustrating that point is a 2024 chemical leak that occurred at the Pemex Deer Park, Texas, refinery. During this incident, contract workers partially opened a flanged connection on piping containing hydrogen sulfide gas, which caused the release and, ultimately, the death of two contract workers and resulted in dozens of injuries. The work was supposed to be done on a different, isolated piping segment located about five feet away from the flange that was opened, according to the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board.

How does that happen? Certainly, the contract workers did not set out to get it wrong that day — there was no malicious intent.

Salas points out that potential risks associated with communication breakdowns or collaborative failures can result in significant safety incidents, environmental damage and human casualties.

Address Teaming Challenges

Organizations can implement several targeted interventions:

1. Comprehensive Team Training: Move beyond superficial team-building exercises toward scientifically validated training programs. These should focus on developing tangible team interaction skills, communication protocols and collaborative problem-solving techniques.

2. Early Skill Development: Integrate teamwork competencies into engineering education and early professional development. This ensures that emerging professionals understand teamwork as an integral component of technical excellence, not a peripheral skill.

3. Regular Team Debriefs: Implement systematic debriefing processes that extend beyond immediate team boundaries. These sessions should provide opportunities for cross-functional learning, error analysis and continuous improvement.

4. Leadership Development: Train frontline leaders to promote psychological safety, facilitate effective communication and model collaborative behaviors.

“People often feel like, ‘I've got to be the one with the answers,’ so they don't ask questions,” Tannenbaum says. “You've got to be technically excellent. You're learning technical skills, you're learning how the piping works, you're learning all this sort of stuff. But if you're not being taught early on that teamwork matters, then it feels like something else different than the work that you do.”

There’s No “I” in Team

"A team of experts does not make an expert team," says Salas. Technical skills get you in the door. Team skills keep you alive and thriving.

Tannenbaum offers a sports analogy: “Imagine a basketball team of all-stars that never practices together, has no shared playbook and constantly rotates players. How well do you think they'd perform? Now replace ‘basketball team’ with ‘chemical processing plant’ and tell me how comfortable you feel.”

Teamwork isn’t about having lunch together and participating in trust-fall exercises. "It's more than that, especially when you have interdependency. You need somebody else's expertise. You need somebody else's knowledge," says Salas.

Importance of Psychological Safety

It is imperative to create an environment where team members feel comfortable asking questions, admitting uncertainties and offering critical feedback without fear of retribution. It’s not new-age jargon meant to illicit the warm fuzzies.

“Psychological safety doesn't mean being nice to everybody all the time,” says Tannenbaum. “It doesn't mean we vote on decisions. It doesn't mean everybody is equal. It means everybody is comfortable speaking up, asking questions and admitting when they don't know something.

“You may have an organization that's doing a really good job and yet you're dealing with a leader somewhere in the organization who doesn't believe in this and who kind of squelches people. And as a result, psychological safety is lower and they're more vulnerable in that spot.”

Tannenbaum has a wish list for industry that includes conducting quick, regular teaming debriefs—not just after mistakes but on an ongoing basis. He stresses the need to establish communication channels beyond immediate team boundaries. Research shows that cross-functional teams — those involving people from different areas across the company— can be very effective, but they need to pay attention to staying on the same page.

Salas reiterates the value of research-backed teamwork strategies.

“Listen, there is a science of teamwork. There is a science of team performance. There is a science of team training. And that science is robust,” says Salas. “It’s not perfect, but it’s robust enough that it can give you tools and strategies that work. And we have evidence of that.”

About the Author

Traci Purdum

Editor-in-Chief

Traci Purdum, an award-winning business journalist with extensive experience covering manufacturing and management issues, is a graduate of the Kent State University School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Kent, Ohio, and an alumnus of the Wharton Seminar for Business Journalists, Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.