Successfully Implement an Operator Care Program

Successful operator care programs improve reliability, quality and safety. They also enhance job satisfaction. By decreasing unexpected breakdowns, downtime and maintenance costs, operator care programs also boost financial performance.

Such programs aim to have operators act as owners of their equipment. They become full partners with maintenance, engineering and management to ensure equipment reaches operational goals every day. Successful operator care programs:

• improve production;

• provide individual professional development;

• promote reliability and safety;

• reduce waste; and

• decrease training and downtime.

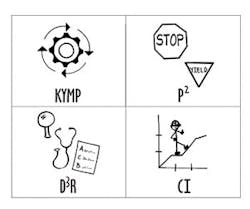

Figure 1. Operator care involves four distinct but complementary aspects.

Operator care has four elements, illustrated in Figure 1, that create a hybrid operator who is comfortable in the operations, maintenance and engineering worlds:

KYMP — Know Your Machine and Process. Operators increase their knowledge of their process and their machines. This may go well beyond current knowledge requirements.

P2 — Prevent or Postpone Failure. Activities to avoid failure include lubricating equipment, hands-on cleaning, tightening bolts and making minor adjustments. We consider this to be basic maintenance work.

D3R — Detect Defects, Diagnose and Report. Inspections directly resulting from the hands-on cleaning activity identify any deterioration or defects.

CI — Continuous Improvement. The operator always is involved in thinking about how to make the equipment work better. Potential improvements may come from reduced downtime, increased yields and lower utility usage. CI is an adjunctive engineering activity.

Implementation Challenges

You will encounter resistance when launching an operator care program. Success demands proactive steps to address resistance as well as a well-designed learning process. Organizations that simply announce a new expectation and schedule a class but do little intentionally and proactively to manage natural resistance or reinforce the desired change in behavior rarely achieve satisfactory results.

The groups typically involved or impacted by the operator care program are: management; operations; maintenance; sales and marketing; and supply chain vendors. People in each of these stakeholder groups will be required to change their behavior.

The stakeholder group most resistant to changes is management, particularly the direct supervisor. This individual also has the most influence over resistance from the operators and other people who must change.

To alter operator behavior to produce the desired results requires integrating the science of change management and learning. This can be achieved by leveraging established models within each discipline. An example is the integration of Prosci’s ADKAR model with our 3A learning process.

ADKAR is a model for the five phases or stages all individuals progress through when they change:

1. awareness of the need for change (why);

2. desire to support and participate in the change (our choice);

3. knowledge about how to change (the learning process);

4. ability to implement the change (turning knowledge into action); and

5. reinforcement to sustain the change (celebrating success).

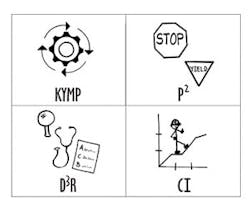

The Life Cycle Engineering (LCE ) 3A Learning process (Figure 2) has three elements — align, assimilate and apply.

Figure 2. This proven model involves three stages.

Achieveing Awareness and Desire

In the first phase of the LCE 3A learning process, we gain alignment by creating a direct line of sight from individual behavior to organizational goals. This is done through an intentional campaign to establish awareness of the business need for change and a desire to alter behavior. Senior leadership most influences awareness while direct supervisors most influence desire. The supervisors should work with an impact map that connects the desired individual behavior to organizational goals. This learning impact map can be a simple table that has columns for organizational goals, learning objectives, individual behaviors and individual results. The objective is to engage the operators’ manager in the discussion and setting of expectations for behavior change following the class. More information on how to implement a learning impact map is given at LCE.com.

Senior leadership will communicate the business reasons for the change. The message should outline the current business environment, including competitor and customer influences. It also should describe the risk of not changing. This communication should make operators and other impacted stakeholders aware of the business drivers for the operator care program.

The supervisor will introduce operator care concepts, pointing out the benefits for the operators’ jobs and lives. Operators will prefer to hear from their supervisor about how the change will impact them personally. The supervisor’s responsibility includes significant activities that require strong communication, planning and leadership skills to accomplish the following steps in rolling out an operator care program:

• conducting the initial education and pitch for the operator care program (to all hands);

• selecting future leaders for deeper training;

• setting up committees and choosing the pilot area;

• establishing targets for the pilot area;

• creating plans for machines and areas;

• organizing the opening ceremony;

• starting training and implementation in the pilot area; and

• implementing techniques, including reporting, incentives, and external and internal support, to sustain the program.

Figure 3. The leader of operator care training sessions requires a good balance of skills.

The supervisor’s actions and communications can make or break your program. First, supervisors tend to be the most resistant to change. So, make a conscious effort to include them in the design and deployment of the program. This will improve their willingness to try operator care and act as advocates for the program. Second, supervisors are the most influential people in overcoming resistance and creating desire among the operators. During this align phase of the 3A process, you want to achieve awareness and desire for the operator care program.

Creating Knowledge and Ability

The assimilate phase is where the capabilities to implement the change are created. This is achieved by delivering learning events (classes) that:

Assess and access prior experience. Every person comes to the class with unique individual experiences. The facilitator should be able leverage or mitigate these inputs. Failure to do so will lead to disengagement and disruption during the learning event.

Engage participants in activities at least 75% of the time. The event should allow attendees to work with and practice the knowledge introduced. Active participation means the learner is reading, speaking, writing or, in some other way, engaging with the content, not passively listening and watching a slide presentation or video.

Provide relevant application experience. Learning should directly relate to helping the attendees do their jobs or reach a goal. Use examples from the workplace, not textbook case studies.

Offer self-direction in the learning process. Adult learners want to be able to choose how they learn. So, let attendees make decisions about what, how and when they will learn. There obviously are some constraints on this. However, never do for learners what they can do for themselves. Seek out ways to let the participants make decisions.

Typically, such sessions should involve no more than 15 operators.

Even with the best course, the particular class leader makes a big difference. That person should provide a good balance between instructor skills and facilitator skills (Figure 3).

The assimilate phase should include engaging the operators in beginning the operator care process for their equipment. The following exemplifies one approach you could apply. It relies on the 5S process (sort, set in order, shine, standardize and sustain).

1. Observe, interview and evaluate by walking down the area, then audit and score.

2. Obtain any current check sheets, preventive maintenance to-do lists, etc. and scrutinize as a team. Review the maintenance logs for history of chronic failure.

3. Take “before” photos.

4. Establish a quarantine area.

5. Initiate a “red tag” process to identify items that potentially don’t demand attention, and sort.

6. Review the red tag log with area team members.

7. Assess what to do with as many red tag items as possible.

8. Determine resources needed.

9. Using the process worksheets, record issues and opportunities.

10. Regroup and discuss what you observed and recorded for improvement. What tasks must be performed? What supplies do we need to do them? Do we need cross-functional support from other work streams?

11. Develop a plan and assign tasks. Obtain supporting documentation for tasks.

12. Review the plan with necessary area workers.

13. Start 5S activities. Simplify. Sweep and clean.

14. Conduct another observation and repeat the audit.

15. Develop the 5S area map with help from the area owner.

16. Implement the 5S board and populate it with help from the area owner.

17. Review and train the area owner on the 5S board responsibilities.

18. Conduct an audit with the area leader, teaching that person what to look for in the audit.

19. Develop operator-care rounds process per flow and step definitions.

20. Establish or revise operator instructions for the operator round.

21. Review with area workers and adjust as needed.

22. Train steps 19 through 21.

23. Develop coaching cards.

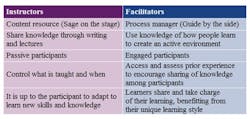

Figure 4. A visual mechanism to show targets and progress can help sustain the program.

Reinforcing New Behaviors

The apply phase is when people begin to attain success. Achieving sustained change in behavior requires reinforcing the new behaviors. When people learn new processes, knowledge and skills, they go through a process that can be divided into three types of learning.

1. The classroom or formal learning event. This often is a live facilitator-led session or self-paced learning exercise given during the assimilate phase. However, the reality is that it amounts to only about 10% of the learning process.

2. It is through coaching and peer support that operators begin to apply what they have learned. During this application process, they pick the brains of their peers or ask a coach, often the same facilitator who led their classroom session. This learning from peers and coaching represents about 20% of the learning process.

3. The most significant stage of learning is doing. Performing actions and learning by trial and error represents 70% of how people learn. Most people gain proficiency in their job by doing it. Yes, formal “book” learning is important, as is the support of peers, coaches and bosses. However, it’s the application of the new skills and knowledge learned in the actual work environment that makes the learning stick.

Do not leave this to chance. Ensure the application phase includes all three types of learning. Design specific, challenging tasks that must be completed and documented.

Early success is critical — this spurs people to use what they have learned and make changes. Management support and coaching are crucial for achieving early wins. Managers can run interference and ensure processes and resources are in place to adapt systems and structures. Coaches can provide the mentoring and feedback to help operators apply what they have learned to the work environment. People are naturally resistant to change but coaching and encouragement can help them to adapt. Management and coaching support are important factors in learning retention, as is the individual’s commitment to put new knowledge and skills into practice.

To make the new operator-care behaviors “stick,” it’s a good idea to establish project targets and publish progress on a dashboard. Figure 4 shows suggested components of such a dashboard.

A strong apply phase ensures participants:

• keep goals top of mind;

• celebrate success;

• plan and track progress;

• learn from others;

• receive coaching and mentoring;

• involve their managers; and

• document results.

Some typical mistakes to avoid include:

• not considering both how people learn and how people best adapt to change;

• focusing only on the learning and, therefore, not getting sustained behavior change;

• trying to change behaviors without teaching operators how; and

• training without reinforcement.

Take Care With Operator Care

Achieving success with an operator care program depends as much upon behavior change as new processes and tools. By keeping Prosci’s ADKAR model for individual change and LCE’s 3A Learning process in mind, you can engage people’s willingness and ability to make the change. The end result will be an operator care program that gives operators more satisfaction with their jobs and delivers improved reliability, quality and safety.

BILL WILDER, M.Ed., is the founder and director of the Life Cycle Institute, Charleston, S.C. JOEL LEVITT is director of international business at Life Cycle Engineering in Charleston, S.C. E-mail them at [email protected] and [email protected].