It's Not 'Just Water:' Understanding What’s Really in Your Supply

Key Highlights

- Pretreatment methods like clarification, coagulation, and flocculation are essential for removing particulates and preparing water for high-purity processes.

- Modern clarifiers and membrane technologies are more efficient and compact, enabling better solids removal and higher water quality for industrial use.

- Comprehensive water analysis, including seasonal and short-term variations, is critical for designing effective and adaptable water treatment systems.

In the 1980s, a popular TV commercial showed a cantankerous man driving down a two-lane road. The vehicle’s tailpipe was spewing smoke and blinding the drivers behind. One of his passengers questioned his choice of motor oil, to which the man growled, “Motor oil is motor oil.” The announcer went on to say “motor oil definitely is not motor oil.”

As I can attest, both from direct experience and from numerous accounts by colleagues, a mindset that appears too often in industry is that “water is water.” Catastrophic boiler tube failures and other difficulties have occurred because of this belief. This series will examine the primary impurities in common makeup water sources for the chemical industry, and it will outline the evolution of water treatment from bulk to high-purity applications.

Water’s Special Properties

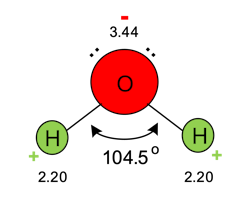

Water is often considered the nearest thing to a universal solvent. Figure 1 illustrates the important details of water’s molecular structure.

Water molecules are not linear, as two pairs of unbonded electrons on the oxygen atom influence the molecular geometry. Oxygen is a highly electronegative element, meaning that it tugs strongly at most other elements’ electrons when bonding. This means that although the hydrogen-oxygen bonds in water are covalent, the electronegative oxygen atom exerts a strong influence on each hydrogen electron, pulling it some distance away from the hydrogen nucleus. This imparts a partial negative charge on oxygen and a partial positive charge on hydrogen. The polarity causes water molecules to be electrostatically attracted to their neighbors in a phenomenon known as hydrogen bonding.

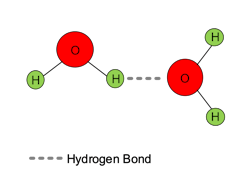

Hydrogen bond strength is only about one-tenth that of the covalent bonds, but the “bonds can have a profound effect on the properties and chemical reactivity in which they occur. ... Water, for example, would boil at about -100°C instead of +100°C if hydrogen bonds did not play their role.” [1] An everyday example is ice formation. As water freezes, hydrogen bonding causes the molecules to form a crystalline structure that has a slightly lower density than the cold liquid. Thus, ice floats. This process is extremely important, as the winter formation of an ice layer on ponds and lakes insulates the water below. Without hydrogen bonding, water bodies in Northern climates would freeze solid during winter.

The polarity of water molecules allows water to dissolve, at least partially, many minerals in the Earth’s crust. Water flows along countless pathways, which puts it in contact with many soils and geological formations.

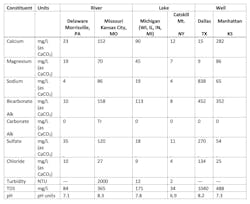

The variable chemistry of freshwater supplies in the U.S. is briefly illustrated in the following table, which provides comparisons between two river water, two lake water and two groundwater sources.

While this table represents only a small fraction of the water supplies around the country, it very much helps to illustrate issues that must be considered when designing water-treatment systems. These items include:

- Some areas of the country, including portions of the Midwest, have large limestone deposits just below the earth’s surface. While the principal components of limestone (calcium carbonate (CaCO3) with usually lesser amounts of magnesium carbonate (MgCO3)) are only slightly soluble in natural water, their presence can still add appreciable hardness and bicarbonate alkalinity to water supplies. This is reflected in the Missouri River sample. Conversely, note the two sources in the Northeastern U.S., one river water and one lake water, that have very low hardness, indicating passage along or through formations with different and very stable mineral compositions. (Consider that the nickname for New Hampshire is the Granite State.)

- As the well-water sample from Manhattan, Kansas, suggests, elevated hardness and alkalinity are common in some groundwater supplies because “once rainwater penetrates soil, it is exposed to CO2 gas levels much greater than in the atmosphere, created by respiration of soil organisms as they convert organic food into energy and CO2.”[3] The extra CO2 increases dissolution of calcium and magnesium carbonate. Additional groundwater impurities may include iron and manganese and sometimes dissolved gases such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Supplies with high hardness may require lime/soda ash softening for primary pretreatment, which adds complexity and cost to the process.

- Other sources may have noticeable salinity, even when not located near the ocean, for example, the groundwater supply from Dallas. In my experience, engineering firms often don’t take chloride concentrations into account when selecting metallurgy for heat exchangers such as steam surface condensers. We will examine this issue later in the series.

- Many river supplies, and especially in locations with substantial topsoil, can see huge spikes in suspended solids during heavy precipitation. The high turbidity of the Missouri River sample clearly illustrates this issue. Surges in solids concentration may cause serious difficulties in pretreatment equipment, such as clarifiers and micro- or ultrafiltration units.

- Many facilities employ cooling towers for various processes. Evaporation is the primary method of heat transfer, but this (mostly) pure water loss causes impurities in the circulating water to “cycle up” in concentration. Vigorous makeup pretreatment may be necessary to protect cooling systems from increased levels of scale- and corrosion-inducing impurities. The reader can find more details about cooling tower operation in a recently concluded Chemical Processing series.[4]

- Although not shown in Table 1, some groundwater sources, and particularly those in the Southwestern U.S., contain silica (SiO2) in double digit (mg/L) concentrations, which, when cycled up in a cooling tower or reverse osmosis (RO) unit, can potentially form tenacious deposits.

- Potentially troublesome in some locations, e.g., bayou country along the Gulf Coast, are large organic molecules produced from decaying vegetation. These compounds can foul RO membranes and ion exchange resins.

- For the many high-purity makeup water treatment systems that have RO as a core technology, dissolved ion concentrations increase at least four-fold from the leading to the trailing elements. Like the concentration increase in cooling towers, this factor requires careful evaluation of pre- and process treatment methods to minimize scale formation.

Two items should always be in the foreground of treatment-system selection. First is that water sources vary widely in quality, and a one-size-fits-all approach to water treatment is not viable. Second, and this is highly important, water-treatment systems should never be designed based on a single water analysis.[5] Seasonal and short-term influences can dramatically alter water chemistry. Cases are known where a treatment system had to be replaced because of faulty or inadequate raw water data.

Raw Water Pretreatment

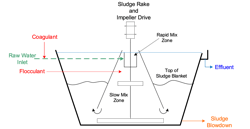

As U.S. industrial capacity rapidly expanded in the last century, clarification followed by effluent filtration with sand or multi-media filters became a ubiquitous pretreatment method for particulate removal from industrial plant makeup streams. Clarifiers utilize both physical and chemical methods to remove suspended solids, as shown in the fundamental schematic in Figure 4.

As will be outlined in Part 2, modern clarifier designs are much improved, but this basic illustration allows straightforward discussion of the fundamental processes.

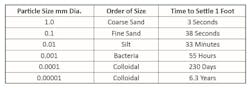

Pretreatment systems typically have inlet screens to remove large materials that would otherwise foul or damage downstream equipment. The remaining particles cover a wide size range.

As can be seen, without assistance fine particulates can remain in suspension for very long periods. Clarifiers were an initial answer to this difficulty. Suspended particles typically have a negative surface charge causing them to repel each other. Coagulation involves the introduction of chemicals to neutralize the negative charges and bring particles close together. Most common are inorganic compounds:

- Aluminum sulfate (alum), Al2(SO4)3•18H2O

- Sodium aluminate, Na2Al2O4

- Aluminum chlorohydrate, Al2ClH7O6

- Ferric chloride, FeCl3

- Ferric sulfate, Fe2(SO4)3•9H2O

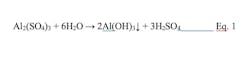

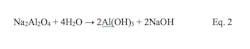

Consider one of the most well-known coagulants, alum, which when added to water reacts as follows:

This equation illustrates two important aspects of alum chemistry. Foremost, aluminum ions combine with water to form a hydroxide precipitate. The gel-like material neutralizes particle charges allowing particulates to move much closer together. Second, this reaction generates sulfuric acid that removes alkalinity from the water and lowers the pH. Alkalinity replenishment of the effluent may be needed. Iron-based coagulants react similarly. Alum functions most effectively within a 5.5-8.0 pH range, while iron salts perform over a broader pH range of 5-11. Since sodium aluminate has the opposite effect of alum on pH, it may be a better coagulant in some applications.

Organic coagulants are also available, and these compounds have a high cationic charge. Examples include polyamines and poly-diallyl-dimethylammonium chloride (DADMAC). Organic coagulants have many active sites, so low ppm concentrations may be sufficient for charge neutralization.

As Figure 5 suggests, clarifiers typically have a rapid mix zone to ensure proper coagulant-particle interaction. Water exiting the rapid mix zone enters an area of lower velocity for flocculation. Flocculants are organic polymers of high molecular weight that act as bridging agents for the coagulated particles.

Depending on the particulates to be flocculated, the polymers may have anionic or cationic sites, or various combinations, including non-ionic sites. For example, polyacrylamides are a common flocculant. In contrast to coagulant mixing, flocculants need gentle agitation to influence the process but prevent the flocculated particles from breaking apart.

Flocculants may be supplied as powders or emulsions. In emulsion formulations, the polymers are often tightly curled and need time to unwind to be fully effective. A technology to accomplish this is a small, external mixing chamber and feed pump that uncoils the polymer for delivery to the clarifier.

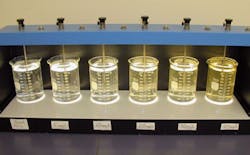

A critical aspect for determining effective coagulant/flocculant chemistry is jar testing. A common apparatus is shown in Figure 6.

Standard procedure is to feed graduated concentrations of the coagulant to the beakers with rapid mixing, and then, after a short period, reduce the mixer speed and inject the flocculant. Jar testing is somewhat of a trial-and-error process to narrow down the best formulations and concentrations. Reputable water-treatment companies usually have experienced people who can assist with this testing.

With proper chemistry and clarifier operation, a stable sludge bed forms in the lower portion of the clarifier as shown in Figure 4. In many designs, the mature sludge serves as a “blanket” to collect newly formed flocs moving upwards through the main body of the clarifier. Upsets, which can come from a change in raw water chemistry, flow, temperature or poor blowdown practices, will allow the bed to expand, with potential carryover of solids to downstream filters. Regular attention to operation is important for maintaining proper effluent quality.

Older clarifiers relied on a large volume (with corresponding large footprints) to provide the needed residence time for flocculation. Rise rates in these units were generally within a range of 0.5 to 1.5 gpm/ft2. Rise rate is the ratio of effluent flow (gallons-per-minute) to the surface area at the top of the clarifier.

Clarifier technology has evolved significantly in recent decades, and modern units usually operate with much greater rise rates, making them more efficient and compact in size. Part 2 of this series will explore some of the important design points. The article also will further detail the evolution of pretreatment, including micro- and ultrafiltration membrane technologies, which are replacing clarification in certain scenarios. They are becoming particularly popular for solids removal ahead of high-purity makeup treatment processes such as RO and ion exchange.

References

- Cotton, F.A., and Wilkinson, G., Basic Inorganic Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1976.

- Perlman, H., Evans, J., The Water Cycle, 2019. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, USA.

- Flynn, D.J., ed., The Nalco Water Handbook, Third Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2009.

- Buecker, B., Aull, R., “Cooling Towers: A Critical but Often Neglected Plant Component – Parts 1-5”; Chemical Processing, September 2024 – December 2025.

- “Fundamentals of Raw Water Treatment”; www.samcotech.com. https://samcotech.com/industrial-wastewater-treatment-guide-expanded-edition/

- ChemTreat, “Chapter 2: Makeup Water Pretreatment Methods,” https://www.chemtreat.com/solutions/water-essentials-handbook-makeup-water-pretreatment-methods/

- Buecker, B., Willersdorf, W., and Shulder, S., “Cutting Edge Concepts for Makeup Water Production”; pre-workshop seminar for the 36th Annual Electric Utility Chemistry Workshop, June 6, 2016, Champaign, Illinois.

About the Author

Brad Buecker, SAMCO Technologies, Buecker & Associates, LLC

President, Buecker & Associates, LLC

Brad Buecker currently serves as senior technical consultant with SAMCO Technologies and is the owner of Buecker & Associates, LLC, which provides independent technical writing/marketing services. Buecker has many years of experience in or supporting the power industry, much of it in steam generation chemistry, water treatment, air quality control, and results engineering positions with City Water, Light & Power (Springfield, Illinois) and Kansas City Power & Light Company's (now Evergy) La Cygne, Kansas, station. His work also included 11 years with two engineering firms, Burns & McDonnell and Kiewit, and two years as acting water/wastewater supervisor at a chemical plant. Buecker has a B.S. in chemistry from Iowa State University with additional coursework in fluid mechanics, energy and materials balances, and advanced inorganic chemistry. He has authored or co-authored over 300 articles for various technical trade magazines, and he has written three books on power plant chemistry and air pollution control. He is a member of AMPP, ACS, AIChE, AIST, ASME, AWT, CTI, and he is active with Power-Gen International, the Electric Utility & Cogeneration Chemistry Workshop, and the International Water Conference.