Is Buying Used Equipment Really A Bargain?

[pullquote]

Used equipment offers two attractions. First, you can avoid delivery delays incurred when ordering some new equipment. This may provide significant schedule savings — even as much as six months or more — in procurement. Having a unit quickly up and running again frequently is worth a lot. Second, used equipment costs less, sometimes a lot less. However, if issues arise with the equipment, cost savings can dwindle or disappear. Getting used equipment to the plant and properly working requires different skills than those for purchasing new items. So, let’s look at potential problems and also a situation where used equipment proved a bad bargain.

First, though, let’s distinguish between remanufactured and used equipment. Remanufactured equipment undergoes reconditioning to a “like new” state by the original equipment manufacturer or a specialist vendor and generally comes with a warranty. Commonly available remanufactured equipment includes control valves and pumps.

In contrast, used equipment mainly consists of items from shuttered plants. You usually purchase such equipment as-is (or perhaps after cleaning) and where-is. The item may have sat idle for years or longer, rarely comes with any warranty or performance guarantee, and often lacks mechanical or process design documentation.

If the name plate is readable, you may be able to get (generally for a fee) original design mechanical details from the manufacturer, if it’s still in business. However, you won’t know the effect of any subsequent repairs or modifications.

The process requirements for the new service nearly always differ from the original ones. You may need expert-level knowledge to decide if the equipment really will suffice.

If you’re fortunate enough to find an item very closely matching what you need, then you can save money. However, don’t count on saving much if you incur significant repair, reconditioning and engineering costs.

The experience of a site that bought a surplus 42-in.-dia. distillation tower exemplifies what can go wrong. That packed column, which had been built at a pharmaceutical plant but never placed into service, had sat idle for years. The tower was sold without any documentation on its internals; no mechanical or process details were available on internals configuration or original design rates, conditions or physical properties.

The tower was loaded horizontally onto a truck, shipped well over a thousand miles to its new home, unloaded and then erected. At no time, did anyone inspect the column’s internal condition.

The tower failed to perform on startup. Troubleshooting quickly ran into hurdles: What were the internals? What range of liquid and vapor rates could they handle? What was their mechanical condition? No one knew.

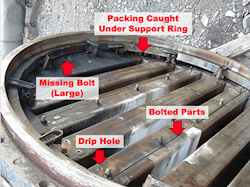

Figure 1. A variety of issues severely degraded the performance of the random packing underneath.

Disassembly of the tower revealed many problems. For instance, the liquid distributor (Figure 1) had very small diameter drip holes; it was designed to handle a much lower liquid rate than the process needed. Second, the distributor had mechanical flanges; this is a low-budget configuration, cheap to make but highly susceptible to leaks that degrade performance. Third, bolts and hardware were missing or perhaps never were installed; this left large holes that would pass lots of liquid and significantly undermine tower performance. Fourth, the tray had come loose from its support ring during transport and some packing had become wedged underneath. Most liquid wouldn’t go down the distribution holes but would leak at the edge of the tower. This dreadful liquid distribution meant the packed bed underneath achieved less than 10% of its possible performance. Finally, the migration of packing to under the distributor also showed that the random packing supports and hold-downs had severe problems.

The plant had to remove and replace all the tower internals. The tab for this made the total cost of the used tower exceed that of a new one. Additionally, the time required for the repairs eliminated any schedule savings.

You can save by buying used equipment — if you do so correctly and can ensure the equipment suits its new service.

ANDREW SLOLEY is a Chemical Processing Contributing Editor. You can email him at

[email protected]