Celebrating International Women In Engineering Day

Transcript

Welcome to a bonus episode of Chemical Processing’s Distilled podcast, where we extract the essential elements from current events and topics we think will interest the CP audience. This podcast and its transcript can be found at chemicalprocessing.com. You can also download it on your favorite player.

I’m Traci Purdum, editor-in-chief of CP.

Did you know that today — June 23 — is International Women in Engineering Day (INWED)? Launched by the Women’s Engineering Society (WES) in the UK in 2014, the event has since grown into an internationally recognized awareness campaign celebrated by various organizations, institutions, and individuals worldwide. Each year, INWED adopts a specific theme to focus on women’s contributions to engineering and STEM. This year’s theme is “Together We Engineer.”

Doing its part in recognizing women in the field, the American Institute of Chemical Engineers features The Women in Chemical Engineering Community (WIC). The WIC Community supports the equitable treatment, representation and employment of all women in chemical engineering.

The institute highlights several trailblazing women, including Margaret Hutchinson Rousseau. Born in Houston, Texas, in 1910, Rousseau began her engineering studies at Rice University before moving on to MIT, where in 1937 she became the first woman to earn a doctorate in chemical engineering at that school. Soon thereafter, Rousseau would make her mark on the profession and the world.

While working at Pfizer in the early years of World War II, Rousseau drew on process design experience she had acquired while producing synthetic rubber and distilling oil into high-octane fuel and designed the first process for producing penicillin on a commercial scale. Her deep-tank fermentation process enabled large-scale production of the miracle drug, which saved countless lives during World War II and became a turning point in human history as the first real defense against bacterial infection.

Lack of Recognition Prompts Project

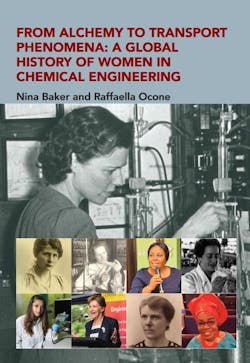

But recognition of women’s contributions to chemical engineering is somewhat lacking, according to Nina Baker, an independent engineering historian, and Raffaella Ocone, professor of chemical engineering at Heriot Watt University in Edinburgh.

In the preface to their booklet, “From Alchemy to Transport Phenomena: A Global History of Women in Chemical Engineering”, the authors wrote:

A while ago, a speaker took to the stage to deliver the after-dinner speech at a major international conference on chemical engineering. It started well enough, with a whistlestop tour of the history of the field in focus and how the conference had developed since its inaugural year. Photos flicked across the screen, showing us the forerunners and leading lights of the field from its inception days through to the present.

But the enjoyment quickly withered to disbelief: there had not been a single mention of a single woman. Was that because no women had made significant contributions to the field?

Driven by this absence, we decided to take the challenge of rectifying this situation by looking at the development of chemical engineering through the eyes of women who have contributed.

The 32-page booklet ponders the definition of chemical engineering and traces roots all around the world to find answers and examples of women succeeding in the field. From ‘Maria the Jewess’ (circa 1st century CE), whose principal claim to fame is the double container for heating things gently over water, to women credited with early chemical work, such as the perfumery of Cleopatra, these examples border on the mythic since no real evidence remains, the authors note.

The authors point out that degrees in chemical engineering weren’t a thing until the late 1800s. According to her research, The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was the first, by a long margin, to establish a degree course explicitly in chemical engineering, starting in 1888. And they also document Rousseau’s accomplishment of being the first woman to gain a PhD in chemical engineering from the Boston school.

The first woman of any nation to not ‘just’ qualify as an engineer but then go on to have a full career in her field is Elisa Leonida-Zamfirescu. After graduating from the Royal Academy of Technology in Berlin in 1912, she identified new resources of coal, shale, natural gas, chromium, bauxite and copper and many of the national standards for analytical work, which she drafted, are still in use today.

BASF's Anne Berg

Looking closer to home and in the 21st Century, it seems fitting to honor the women who have participated in Chemical Processing’s podcast episodes. Through the years, I’ve interviewed several engineers, and I’ve put together a compilation of their insight and advice.

At the beginning of the year, I spoke with Anne Berg, vice president of Manufacturing, Agricultural Solutions Americas at BASF. At the time, Anne had recently been inducted into the Women in Manufacturing Hall of Fame. Her remarkable 28-year career spans multiple countries and roles. Starting as a process development engineer in Germany in 1996, she has worked in manufacturing leadership positions in Germany, Belgium, Spain, and the United States.

A key piece of advice she offers young women is to remain open to unexpected opportunities and not adhere too rigidly to a predetermined career path.

Here’s a few snippets from that interview.

Traci: You mentioned you went to the one plant, and they did not even have a women's restroom. Not for any other reason; they just didn't have a need for it in the facility. Let's talk a little bit about some key challenges or barriers that women face in entering and advancing careers in the chemical industry.

Anne: Yeah. I think luckily in most areas we are over that point that they need to build the facilities. Still there is rooted deep in many of us is this belief that men are more for the technical professions and women are more for other professions. And there's more and more people opening up to these thoughts. I would call it naive when I started, I thought I'm just myself. I like engineering, I'll do that. So in many situations I was the only woman in the room, but honestly I didn't notice it. Which has its advantages, if you just don't think about it, you don't think too much about the differences and you find the common topics and just what you need to address what you're talking about, what your topic is about. There is also, I think, a danger in being too naive and not looking at it at all.

Traci: Are there any personal learnings that you've brought to the table based on gender diversity? Something that would not have happened without that diversity?

Anne: There are topics, and for me, the one that strikes me the most and I observe repeatedly, and you might be able to relate to that one, there is this challenge between being assertive and not being perceived as aggressive. Where there is definitely a different perception based on gender. Which is, I don't think it's intentional by anyone, but it's a challenge I am facing and other women are facing when you are, by nature, you know what you're doing. You want to be assertive and you are assertive, it can easily be perceived as being aggressive or even a not so good person. While for a male it might be rather, oh, they know what they are doing, they want to have this, they're just assertive. So that's for me, personal learning where I am way more observing myself and a little bit on the watch-out that I don't fall into the trap or that I make sure that I am not perceived as too aggressive while I only want to be assertive. There are ways around, but sometimes when you have the personality and you are rather assertive by personal trait, there is the risk of being perceived like that.

Traci: What advice would you give some young women considering going through your career path?

Anne: My first advice is always be open and grab opportunities. So there is a balance between, in my opinion, what you can plan for and what you might want to decide spontaneously along the way. And my career was largely unplanned. I know not everyone wants to have it that unplanned and I think a little bit more planning might not be a totally bad idea. But I grabbed the opportunities when they were there, I was open to that and I was motivated to do that and I also had the ability to do it. That's not always the case. And a little bit of a plan is definitely helpful, but I think not having a too clearly outlined path and only one straight line in mind, but to allow for what could be another option, what could be a turn that I might want to take. And then let's see where it leads me is a good idea.

Safety Guru Trish Kerin

If you are familiar with the Process Safety with Trish & Traci podcast, then you are already familiar with Trish Kerin. Trish, a mechanical engineer based in Australia, is the former director of the IChemE Safety Centre and now leads her own company: Lead Like Kerin.

Early on in the process safety podcast series, I sat down with Trish to understand how she got to where she was in her career. Let’s listen in.

Traci: Well, today, we're going to get a little bit personal, at least in terms of how you landed in your current role. Obviously, you don't just apply for the job of director of the IChemE Safety Centre. There has to be a path that led you there, and as with any practice, skills are learned because things don't always go right. Can you walk us through your career and things you've learned the hard way? I know you started out as a mechanical engineer designing and installing aviation fueling systems, so can you walk us through how you got to where you are today?

Trish: Sure. So, it was a long and winding journey, I would say. I'd never really had a career plan of where I was going to go. And, in fact, the reason I studied engineering was simply because it was a sort of degree that you could go and get a job from rather than have to go and do some other form of study or some other form of training to actually become a professional in an area. So, that's why I did engineering in the first place. I got a job in an oil company. I started doing, as you said, the design and construction of aviation fueling systems. And that was a really fun job. I loved working at airports. I loved working in the fueling systems. Thinking back in hindsight, that was the first job I was in when I had my first process safety incident. And fortunately, no one was killed in the incident, and no one was seriously injured. There was a minor injury.

In fact, it was actually to me, the minor injury in the end. And it was an interesting situation. I was building a fueling hydrant system, and we were at the stage where we were reconditioning the line. We were starting to refill the line with Jet A-1 fuel, and so we were venting it a high point in the line into a truck. And we'd rented out enough content. It was time to shut that system down because we'd re-packed the line with jet fuel. And we went to shut the isolation ball valve on the hydrant system, and it wouldn't shut. We couldn't shut off from where the hose was connected to the truck. And no matter what we did, we just couldn't shut that valve.

And so, in my youth, I thought, "Well, there's a dry break coupling connected to this too. Let's just disconnect the hose. That will shut, and at least we can disconnect the truck because we've still got jet fuel flowing into the truck, and the truck is about to overflow." So we then disconnected, and the dry break coupling didn't close either. So, at that point, we actually had a jet fuel fountain happening, which is never a good thing.

Traci: Now, would Trish today in that role do anything different?

Trish: Yeah. Trish today would measure every single assembly and make sure it was put together the right way. But that's something you learn over time, you know. Trish at the time was one year out of university, a very young engineer, a very young engineer who probably thought they knew it all because let's face it, I'm one of them. Most engineers, we come out of university, and we think we know it all. We very quickly discover we actually know nothing, and we need to learn. And you get a little bit of humility along the way and discover that other people know a lot more than you do, and you need to listen to them. And that's part of the maturity process, I think. But, yeah, Trish today would do things very differently, I think.

Crime Novelist & Engineer Fiona Erskine

In another episode of Process Safety with Trish and Traci, Fiona Erskine, an engineer and crime novelist with a passion for process safety, joined us to discuss her work in engineering and writing and how she uses her novels to educate readers about process safety and engineering concepts. Her Dr. Jaq Silver series combines thrilling plots with accurate technical details, making complex topics accessible to non-experts.

I asked her what came first, her desire to become an engineer or a crime writer?

Fiona: Now, I'm definitely an engineer first, without a doubt. Engineering is what I really enjoy doing, and it's certainly better paid as well. It is quite handy. Poor old writers, it's a bit of a tough gig. But no, I'd never really thought about writing. It never even occurred to me, but I've always enjoyed finding different ways to communicate. In fact, one of the early conversations that Trish and I had was about Ramin Abhari, who does these fantastic graphic novels. And it was just such a novel; I had come across his Flixborough graphic novel, and I thought it was just such a great way of trying to tell quite a difficult story in a novel way. And I've passed that on to lots of people who've really enjoyed it.

So yeah, it's just really, I just, I love what I do, and I suppose my crime series are thinly disguised attempts to persuade you that what we do is really, really interesting. And you don't have to be a pop star, or a game show host, or a model to have really fantastically exciting and interesting jobs with lots of international travel. So I guess, yeah, that's really what that kicked it off, just trying to share how much I enjoy what I do. And just briefly, I mean, my huge inspiration was Primo Levi. Primo Levi wrote "The Periodic Table" short stories about his world as an industrial chemist. And because he's such a fantastic writer and poet, he managed to make the mundane just seem really, really interesting. And it's a book I often give to people who ask me what I do.

Traci: So, you do have this other life that they may not understand. I was reading your website, and you state that you write about the road less traveled, and you even quote Robert Frost's “The Road Not Taken,” "Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, and sorry I could not travel both." Do you feel you've traveled both, you are a successful engineer and a successful writer, or do you feel that those are still both roads that are less traveled by?

Fiona: So that's interesting. I love that poem, and I think it's a really interesting quote. I think what I meant by that was rather that we don't write enough about the real world. We don't write about work, and there are so many great books about personal relationships and all sorts of things, but there's very little written about the realities of work. And I think sometimes when we're looking at human factors, when we're looking at all sorts of things in process safety, we don't have a lot of good examples where we can just go and pick something up, and say, "Something went wrong, but the person who did the wrong thing was trying to do 17 different things, all of which appeared to be equally urgent."

So yeah, I think, in part, I just wanted to write more about the materials in the world around us, the decisions that are made for us sometimes about energy, about environmental protection that people are surprisingly incurious about until something really bad happens. So I guess I was more sort of saying, I think, manufacturing is fascinating, and look at how the world has changed in 250 years, the things that we just take for granted now. The fact that, Trish, you're in Australia just now, and Traci, you're in the US, and I'm in the northeast of England, and we can sit and talk to each other. So, so much has changed, and I just wanted to write a little bit more about that.

Cheryl Bodnar Plays the Safety Game

Another great guest and woman engineer was Dr. Cheryl Bodnar, associate professor of Experiential Engineering Education at Rowan University, one of the brilliant minds behind "Contents Under Pressure," an immersive game designed to teach process safety.

Cheryl and the team won the 2023 David Himmelblau Award for Innovations in Computer-Based Chemical Engineering Education.

I asked her how the team got together and what was the spark that ignited the game.

Cheryl: This actually started back in June of 2016. Our group was actually together at the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference at the Chemical Engineering Education Banquet. And the group of us knew each other from previous interactions through the American Society for Engineering Education. We'd also crossed paths as part of the American Institute of Chemical Engineering, and what we noticed was that we all had a passion for looking at new and innovative ways to teach.

We had a discussion as part of our awards dinner, sitting around the table talking about wouldn't it be interesting if we could use a game to teach something in the chemical engineering field. And we were thinking about what types of topics would resonate the most or have the most impact. We circled around to how important process safety is in our students' education and how it's one of those topics that you can't necessarily allow students to go and experience and make mistakes with while they're in the field because there's such serious implications associated with that from a community and environmental standpoint. Then, the idea sparked that, "Oh, this could be the perfect testing bed for using a game in order to teach that type of content."

I also asked her how teaching ethical reasoning benefits process safety.

Cheryl: Sure. I think it's really about broadening the awareness of these situations that occur routinely within professional practice. We talk to the students now a lot about what's called ethical fading, which is the idea that when you're in an educational environment and you see these case studies that are presented to you, you know that you are dealing with an ethical case study, so automatically you put on your ethics hat. So, you go into it, and your decisions are very different because you're focused on the ethics piece.

But as we've talked about throughout this entire podcast, when you're in a practice environment, oftentimes, there's no warning light, there's no sign that goes on, there's no special sound effect that alerts you that the choice that you're about to make has ethical ramifications. So, by getting students familiar with the idea that when you're in an environment, you're going to be faced with many different decisions that are going to challenge you, and you won't always know that there's ethical implications associated with it, but it's about taking that step back and going, "Okay, what are the factors that are influencing this decision that I'm about to face? Are there any things that I know could be potential limitations based on my experiences that I've had so far, and how do I take those into account or mitigate for them so that I don't let them influence my decision unnecessarily?"

As we celebrate this International Women in Engineering Day, the world thanks you for your contributions, which have transformed modern life through innovations touching nearly every aspect of human existence. Together, we engineer.

Subscribe to this free podcast via your favorite podcast platform to learn best practices and keen insight – you can also visit us at chemicalprocessing.com for more tools and resources aimed at helping you achieve success. On behalf of all women in engineering, thanks for listening to Chemical Processing’s Distilled podcast.

About the Author

Traci Purdum

Editor-in-Chief

Traci Purdum, an award-winning business journalist with extensive experience covering manufacturing and management issues, is a graduate of the Kent State University School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Kent, Ohio, and an alumnus of the Wharton Seminar for Business Journalists, Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.