Are you certain about uncertainties?

Last time (CP, October, p. 57), Dr. Gooddata discussed the five types of systematic error (bias) and commented on how important it was to estimate their potential magnitudes or systematic uncertainties (bias).

Note the ambiguity of the term bias. Many people use it to refer to the systematic error for a single measurement. They say bias to mean the actual difference between their measurement and the true value of the test. In contrast, others at times will estimate the potential magnitude of this type of error and call that the bias. Here they mean the +/- interval about the measurement that estimates the possible extent of the true systematic error.

Confused? So am I. Dr. Gooddata, therefore, recommends that we largely abandon the term bias. Instead, we will use the terms systematic error and systematic uncertainty. Systematic error is the actual error that exists between a measurement and the true value with zero random errors. Systematic uncertainty is taken to mean the estimate of the systematic errors limits that we could expect with some confidence.

Collective wisdom

The International Standards Organizations (ISO) Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement recommends that uncertainty analysts (thats you) assign both a distribution and a confidence interval to each systematic uncertainty estimated. The U.S. National Standard on test uncertainty, ASME PTC19.1 Test Uncertainty, has been rewritten and recommends that estimates of systematic uncertainties be assumed to represent a Gaussian-Normal distribution and be estimated at 68% confidence. (That would make systematic uncertainties estimates of one sx, as the degrees of freedom are assumed to be infinite for each of these systematic uncertainties.)

Remember, too, that the combined effect of several sources of systematic uncertainty is still determined by the root-sum-square method. The result is the interval that contains the true value 68% of the time in the absence of random errors (whose limits we now estimate with random uncertainties.)

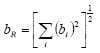

The systematic uncertainty of the result would then be:

where each bi is a 68% confidence estimate of the systematic uncertainty for source i. This allows us to work with equivalent sx values throughout this analysis. We will need that capability when we also deal with the random uncertainties.

As for those random uncertainties, the latest U. S. National Standard recommends (as does the ISO Guide) estimating their magnitude limits as one standard deviation for the average at a particular level in the measurement hierarchy. That is, the random uncertainty for an uncertainty source is the standard deviation of the average for that uncertainty source. It is noted as one sx. Here too, the random uncertainty for the test result is the root-sum-square of the random uncertainties for each level in the measurement hierarchy.

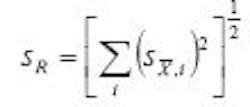

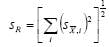

The random uncertainty of the result is then:

where each x,i is the standard deviation of the average for that level in the measurement hierarchy.

Note that with this approach we are working with equivalent sx values for both systematic and random uncertainties. Why is this important? How does this help us? Lets see.

A singular task

Now that we are all experts in the determination of the systematic and random uncertainties of a measurement, the question we must approach with exceptional anticipation is this: What good is it to calculate only systematic and random uncertainties? Shouldnt we find a way to combine them into an overall uncertainty for the measurement result? (I know thats two questions.)

For a long time there were two primary approaches to this problem of calculating a single number to represent the measurement result uncertainty. Those two uncertainty models (kind of like Ford and Chevy for car buffs) were the UADD and the URSS models. These were also known as U99 and U95, respectively, because the former provided approximately 99% coverage and the latter approximately 95%.

Well, what were these models and isnt there something better after all these years?

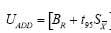

The UADD model was:

The URSSmodel was:

Note that when it is said that UADD provides approximately 99% coverage (not confidence) andURSS approximately 95%, the key words are approximately and coverage.

We use approximately because these coverages were determined by simulation, not statistics. They are right in the long run, but not exact. Why do we use the term coverage and not confidence? What is this coverage thing? Why not express these uncertainty intervals (hint, new word there) as confidence intervals? The reasoning is: The systematic uncertainty, BR, was an estimate of the limits of systematic error to about 95% coverage. BR was not a statistic but an estimate. is, however, a true statistic. It is appropriate to speak of confidence only with a true statistic.

, with a non-statistic, BR. The result cannot be an interval (that new word) with a true confidence but rather provides coverage as documented by simulation.

Both of the above uncertainty equations combine a statistic,

Until now, our emphasis has been on grouping uncertainty sources as either systematic or random. The ISO in its guide does not recommend grouping uncertainty sources or errors that way. Instead, it suggests grouping them as either Type A, where there are data to calculate a standard deviation, or Type B, where there arent. This approach seems in conflict with the commonly applied terminology of systematic and random uncertainty sources.

Emerging approach

However, a new uncertainty model that combines the best features of both methods is now coming into vogue. It handles the ISO recommendations of using Type A and Type B classifications and still allows the engineer to quote uncertainties in the more physically understandable vocabulary of systematic and random. How can this be? What compromises were reached? Tune in next time for the rest of this story and the answers.

For now, though, lets review the basic principles of each model.

Well start with the ISO model. For Type A uncertainties, data can be used to calculate standard deviation. Type B uncertainties must be estimated in some other way. The total uncertainty, which ISO calls expanded uncertainty, is then calculated by root-sum-square of the two types of uncertainties. But first, all the elemental Type A and Type B uncertainties are combined by root-sum-square. That is, we first calculate:

.

and then:

Note here that the UB,i need an assumed distribution and degrees of freedom. The new U. S. National Standard published by the ASME recommends that you assume the UB,i are normally distributed and have infinite degrees of freedom.

It is also important to recognize that all the UA,i and UB,i uncertainties are standard deviations of the average for that uncertainty source that is, they all represent one .

We then need to combine the UA and UB uncertainties into the total or expanded uncertainty. That expanded uncertainty is:

.

The constant out front, K, is used to provide the confidence desired. The most common choice for that constant is Students t95, which provides an uncertainty with 95% confidence. This ISO expanded uncertainty would then be written:

.

A question of degree

Before the Students t95 can be determined, there is one more important step. Do you know what it is? The degrees of freedom for UISO are needed. How do we get that? Well, each standard deviation of the average weve used in the UA and UB equations above has its associated degrees of freedom. For the UA, the degrees of freedom come directly from the data that are used to calculate the standard deviations of the average, that is,

represents degrees of freedom, sometimes abbreviated as d.f.

where

These degrees of freedom are for all the UA,i where Ni is the number of data points used to calculate the standard deviations of the average.

For the UB,i, the degrees of freedom are assumed to be infinite.

The degrees of freedom, , for the UISO is computed for the total uncertainty with the Welch-Satterthwaite approximation:

This formula is a real pain. Hand calculations are very frustrating here. So, program the formula on your computer. One simplifying aspect is that one term in the denominator, , is zero when the

is infinity.

Now, with the degrees of freedom, the Students t95 can be found in a table in any statistics text. Not a problem.

If 99% or some other confidence is desired, just use the proper Students t.

Well, there you have it. Now, we need to consider the U. S. Uncertainty Standard and how to calculate that uncertainty. What are its major components? Hint, they are associated with the impact of uncertainties on the test result. Second hint, these groupings are familiar to engineers the world over. Do you know what they are? Next time....

Until then, remember, use numbers not adjectives.

Ronald H. Dieck is the principal of Ron Dieck Associates, Inc., Palm Beach Gardens, FL. E-mail him at [email protected].