Faster and Cheaper Product Development Beckons

A university spin-off in the U.K. is taking a radically different approach to chemical development. Instead of creating materials in the laboratory and then seeing if they provide desired properties, Quantum Genetics, Newcastle upon Tyne, starts by having customers define the traits wanted and uses computational chemistry to create molecules with those attributes.

Researchers at Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, started doing actual projects using the approach more than two years ago — the school founded the spin-off company in January to commercialize the technology.

Quantum Genetics relies on what it calls Quantum Directed Genetic Algorithms (QDGA).

"The process is conducted primarily in the computer and intellectual domains," explains Dr. Marcus Durrant, pioneer of QDGA and technical director of Quantum Genetics. "This means that as well as focusing on the chemistry of a required application, traits can also include almost anything inside and outside normal experimental domains, such as commodity price and volatility, environmental impact, boiling point, toxicity and weight. This ability to consider a wide set of key issues in the early phases of product development can have a radical and disruptive impact on the cost of bringing new products to market."

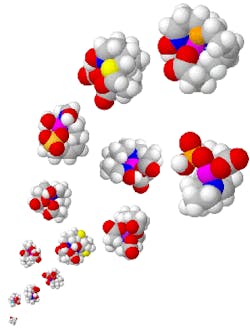

The QDGA approach resembles the biological process of mutation and selection. First, Quantum Genetics staff research known information about qualities the final molecule will need. Then, the team selects candidate molecules with potential to evolve in the desired direction. If prior research is limited, the process can start with randomly selected molecules lacking the desired properties. The most suitable molecules that emerge are used to run the process again; iterations continue until molecules with the desired properties are created (Figure 1).

The first part of the process — a business feasibility study — typically takes four to six weeks and costs £20,000 (about $30,000), while the overall project can take as little as six months, but an average project requires 18 months, notes Graham Hopson, commercialization manager. "A typical cost for a basic project is about £200,000 [approximately $300,000]… at least one-fifth of the cost of an equivalent traditional discovery process," he adds. "It allows you to investigate areas of commercial value that would otherwise be prohibitively costly."

Deliverables from the effort include a list of molecules with the desired attributes as well as an economic exploitation plan. Quantum Genetics also can do all necessary wet chemistry follow-up.

"I think the most interesting aspect of QDGA and the thing that our clients are most interested in is the impact on IP [intellectual property] creation. QDGA's top-down nature allows companies to patent many candidates or a general case, thus denying alternative routes to discovery for competitors," says Hopson.

The developers reckoned that opportunities in polymer chemistry would generate most initial interest. Instead, however, commercial studies so far have focused on food and beverages, consumer chemicals and personal hygiene. Two multinational companies already have commissioned work.

"In general, the applications that are likely to deliver the most value are major challenges that have never been successfully addressed but for which there is a lot of background literature. This is good news because these are applications that tend to have big economic benefit. Two 'big hitters' that we are currently looking for partners for are the catalytic production of hydrazine and the conversion of methane to methanol," notes Hopson.