Opinion: Climate Science Facts Demand Global Consensus, Not Mandates

I'll separate some facts from fiction about global warming. This is done without attempting to take sides and with some assistance in gathering data from AI.

A scientist named Svante Arrhenius (1859-1927) was the first to argue that minor variations in trace elements in the atmosphere could influence Earth's atmospheric heat budget. Studies by NASA of Venus and spectrophotometric analysis of its atmosphere have led to significant concerns about the role of CO2 and other greenhouse gases regarding global warming.

The most significant greenhouse gas is the one we can control the least — water vapor. The relative warming effect of different greenhouse gases is measured using global warming potential (GWP). The GWP compares how much heat a given mass of gas traps in the atmosphere over a specific period (typically 100 years) relative to the same mass of carbon dioxide. By definition, carbon dioxide has a GWP of 1. This highlights the crucial distinction between the natural greenhouse effect and anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change.

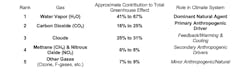

Water vapor is the most dominant greenhouse gas overall but is not counted because we cannot control it. Here is a ranking and quantification of greenhouse gases, relative to water vapor's role:

This ranking reflects how much each gas contributes to the current total warming of the planet, which keeps Earth habitable (the Greenhouse Effect).

Water vapor causes clouds that affect the albedo of Earth by reflecting sunlight and cause global cooling. The effect of clouds is estimated at 50 watts per square meter.

Below is a list of the approximate GHG contributions of the other gases.

This ranking reflects how much each gas contributes to the current total warming of the planet, which keeps Earth habitable (the Greenhouse Effect).

The largest greenhouse gas emitters by country are:

- China — 29.2%

- U.S. — 11.2%

- India — 7.3%

- EU — 6.0%

- Russia — 0.8%

The world's oceans act as a massive carbon sink, reducing the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere. The oceans reduce the atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2).

Quantification of Ocean Absorption vs. Anthropogenic Emissions

The oceans have absorbed a large amount of the excess CO2 emitted by human activities, preventing atmospheric concentrations from rising even faster.

The Key Takeaway: The ocean has absorbed roughly one-quarter of all human-caused emissions over the past decade, acting as a crucial buffer against climate change.

Ocean's Role in Greenhouse Gas Dynamics: The Ocean Carbon Sink (Absorption)

The ocean's ability to absorb greenhouse gases is primarily governed by the partial pressure difference between the atmosphere and the surface seawater as it tries to absorb the gas and restore equilibrium.

CO2 dissolves into seawater, reacting with water to form carbonic acid (H2CO3), which dissociates into an acid by shedding one hydrogen atom. This absorption leads directly to ocean acidification. The ocean naturally exchanges approximately 90% of carbon with the atmosphere. Before the industrial era, this exchange was nearly balanced, resulting in stable atmospheric concentration. It is not possible to quantify the ocean's uptake by country in the same way that emissions are counted.

The ocean sink is a global physical and chemical process that operates based on large-scale ocean circulation and thermodynamics, not on national boundaries. Here are the most important carbon sinks:

Countries with the largest adjacent ocean areas (such as Canada, Russia, the U.S. and Australia) have no special "claim" on the absorbed carbon, as global currents rapidly mix and redistribute it across the globe.

The ocean also helps regulate atmospheric temperature by absorbing and storing excess heat. Some scientists estimate that the ocean has absorbed over 90% of the excess heat accumulated in Earth's climate system since the 1970s.

By comparison, the atmosphere and land masses have absorbed less than 5% of this heat. The ocean's heat absorption is not uniform. Upper layers warm faster than the deeper ocean (depths greater than 700 meters). As the water warms, it expands, contributing to sea level rise.

Since 1850, the pH of the ocean has decreased from 8.17 to 8.07, which impacts the availability of calcium carbonate to shell-building marine life such as oysters and shellfish.

Challenges to Estimating Greenhouse Gas Effects

There are many challenges to developing an accurate estimate of the effects of greenhouse gases and global warming.

First, the available data suffer from scarcity and geographic bias: The climate system is immense, yet observational records are unevenly distributed, leading to data scarcity in crucial areas.

Historical climate records are much denser and longer in North America and Europe than in remote, under-resourced regions like Africa, the deep ocean and the polar regions (Arctic and Antarctic). This geographical selection bias affects the reliability of projection models.

Obtaining long-term, high-quality data from the deep ocean is extremely challenging due to technical and cost constraints, which affects model parameters related to ocean heat uptake and circulation.

We only have access to reliable, truly global data (primarily from satellites) since the late 1970s or early 1980s. The length of the record is too short to accurately predict the future, and models must be validated against a much longer history of natural variability.

The nature of collected data often limits the model's ability to resolve important physical processes. Observational datasets often suffer from measurement bias and inconsistency over time. Early sea surface temperature measurements were taken using buckets, less accurate than modern buoys or satellite measurements. Changes in instruments and data processing algorithms over decades make it difficult to establish a single, reliable long-term trend needed for model validation.

Climate models operate by dividing the atmosphere and ocean into three-dimensional grid cells, but many vital processes — like the formation of individual clouds, turbulent mixing or the specific behavior of vegetation — occur at scales much smaller than these grid cells. The models must use parameterizations (simplified mathematical approximations) based on larger-scale variables. The accuracy of parameterizations is directly constrained by the availability of representative, small-scale observational data: Errors in cloud parameterization are a major source of uncertainty in global cooling projections.

Even if perfect data existed, current computing power limits how existing data can be used. Achieving the resolution needed to reduce reliance on parameterization makes computational cost astronomical, and the desire for higher spatial resolution with the need to run simulations over long time periods and across numerous scenarios forces necessary tradeoffs.

Climate models are validated by running them backward to see if they can replicate historical observations. If observational data used for validation is sparse or biased, scientists' ability to make accurate estimates and determine the range of uncertainty in future projections is impaired.

The data's spatial limitations, combined with computational limits, create fundamental uncertainty in climate models, creating a wide range of plausible climate outcomes based on slightly different initial conditions, assumptions and parameterizations.

Summary

There is a lot of misinformation and scare tactics over the long-term impacts of air emissions on the environment. Some of the predictions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) may come to pass. Others may not.

One point that needs to be made is that governments and political parties tend to support and fund projects that produce results favorable to their objectives and goals. Without casting aspersions at the scientists and researchers who have worked hard to prepare the IPCC reports, the global warming phenomenon is real, and we have observed changes. The conclusions of the IPCC should be viewed with slight skepticism for the reasons cited above. Our measurement system is less than complete, with large gaps in both the record and the areas where measurements can be or are being made. Despite scientists' best efforts, model inaccuracies may be significant.

Any extreme measures taken to limit greenhouse gas emissions may have adverse effects on the U.S. and global economies. Extreme, life-changing mandates to reduce greenhouse gases may have a marginal impact on overall emissions. Changes in greenhouse gas emissions cannot be successfully mandated or imposed by executive fiat. Real change comes about successfully through the implementation of consensus.

Each country has its own agenda and interests, both military and political. There is not much one country can do to achieve a significant impact on global warming. That does not mean we should be disinterested or give up all hope, but we need to push for research to find economical methods of reducing and controlling greenhouse gases. We also need to consider alternative energy sources and the development of clean-burning fuels.

About the Author

Dave Russell

PE, ASP, president, Global Environmental Operations Inc.

Dave is a PE and Associate Safety Professional who practices from his company Global Environmental Operations Inc. He has lectured and consulted on environmental and safety issues all over the world.