Opinion: Why the EU’s Environmental, Social and Governance Standards are Misguided

There’s an old industrial saying that states: “If you can’t measure it, you can’t control it!”

For the purposes of this column, I’ve rephrased it to state: If you can’t measure it accurately, how can you control it?

The European Union has come up with a bad idea in the name of protecting the planet and its people: Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reporting (1). It’s a group of categories lacking standards to rank corporations and countries for the quality and desirability of their investment and operations. It could be compared to academic rankings and class standings. The “best” companies get the highest marks and may have easier access to investment capital, while the lowest-ranked companies may have investments withheld until they obtain a higher ESG score.

In many instances, the ranking is arbitrary because there are few, if any, meaningful standards that could apply in making an investment decision. The intent is well-meaning, but I believe the effort to develop a single number by which to judge the behavior of a corporation is like asking a gym teacher to rank a group of students for academic prowess when he or she may see them only in the gymnasium. The rating includes three sections that measure long-term competitiveness based on the following factors:

1. Environmental (E) considers a company’s ability to protect, harness and supplement its natural resources and manage environmental vulnerabilities and externalities.

2. Social (S) factors in a company’s ability to develop a healthy, productive, stable workforce; the company’s knowledge capital (the value of our corporate and manufacturing knowledge); and the ability to create a supportive economic environment.

3. The governance section (G) of the rating considers a company’s capacity to support long-term stability and functioning of its financial, judicial and political system (how companies decide who is right or gets promoted and “office politics” and its ability to address environmental and social risks.)

Also, corporate objectives and activities must be aligned with the EU Taxonomy: The taxonomy is “a classification system for organizations to identify which of their economic activities, or the economic activities they invest in, can be deemed ‘environmentally sustainable,’” according to the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance.”

Why the Standards are Flawed

The problem with the taxonomy and the standards lies in the details, and the fact that many of the criteria are subjective, lacking specific numerical goals against which the performance of a company can be judged.

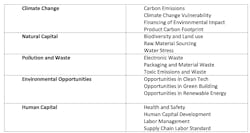

For example, consider the environment and the human capital pillars of the ESG program. The environmental pillar has four subdivisions: climate change, natural capital, pollution and waste and environmental opportunities. The human capital pillar also has four divisions. Within those four subdivisions, there are a number of key issues upon which a company will be evaluated. I selected some of the pillars and themes to highlight some of the areas of concern.

The ranking system is complex. It also appears to be subjective, and that raises the point of the qualifications of the person doing the ranking and the individual’s qualifications. The area of carbon emissions is controversial enough, and there is a substantial body of controversy about what goes into the carbon footprint of a particular product.

The International Organization of the Securities Commissions (2) (FR09/21, November 2021) determined that:

• There is little clarity and alignment on definitions, including what ratings or data products intend to measure.

• There is a lack of transparency about the methodologies underpinning these ratings or data products.

• While there is wide divergence within the ESG ratings and data products industry, there is uneven coverage of products offered, with certain industries or geographical areas benefitting from more coverage than others, thereby leading to gaps for investors seeking to follow certain investment strategies.

• There may be concerns about the management of conflicts of interest where the ESG ratings and data products provider or an entity closely associated with the provider performs consulting services for companies that are the subject of these ESG ratings or data products.

• Better communication with companies that are the subject of ESG ratings or data products was identified as an area meriting further attention given the importance of ensuring the ESG ratings or other data products are based on sound information.

Standards Based on Hysteria

We have seen this type of well-intentioned effort to bring greater scrutiny to the manufacturing sectors before. ISO 14001 is the environmental standard that commits companies to “continuous improvement.” Even so, an industry can have significant environmental violations and still be an ISO 14001 certification recipient. The phrase, “We are working on cleaning up our act,” only goes so far. The ISO 45001 standard appears to be similarly flawed. Both programs seek compliance with their respective country’s legal standards, and therein lies the critical flaw.

When examining the human capital portion of the pillar, it’s clear there is much room for interpretation on the success of a company’s health and safety program, human capital development program, supply chain and labor standards. More significantly, a lot depends upon the personal opinion of the auditors.

In the environmental areas, the carbon footprint issue and global warming standards are also controversial. There is a significant influence of CO2 emissions on global warming, but there is a lot of controversy about the speed with which the world must reduce CO2 emissions and the amount of the contribution, and reductions each country must make by whatever future date seems reasonable.

A recent book “Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn't, and Why It Matters” by Steven E Koonin, who served as the Energy Department’s undersecretary for science during the Obama administration clearly indicates the hysteria of the climate-change crowd and the political nature of the debate outside of science. Modeling does not support the hysteria, and scientists are unable to accurately predict the behavior of the very complex world environment.

Are there concerns? Yes. However, modeling science is not yet developed to the point where it can effectively prognosticate the future a few years out or accurately measure the state of carbon emissions almost anywhere. The question of which countries and industries are the greatest emitters of carbon and what their countries are going to do to reduce carbon emissions while maintaining economic growth and prosperity is still a long way from being settled.

About the Author

Dave Russell

PE, ASP, president, Global Environmental Operations Inc.

Dave is a PE and Associate Safety Professional who practices from his company Global Environmental Operations Inc. He has lectured and consulted on environmental and safety issues all over the world.