Few people would disagree that a well-maintained plant is a reliable plant — and a reliable plant is more likely to be a profitable plant. Yet few would disagree either that companies traditionally have shown a reluctance to invest in plant maintenance. The reasoning, apparently obvious at least to those making the decision, was that such spending comes straight off the bottom line and so cuts into the profit margin. Many engineers certainly know of plants suffering from that spurious economic logic.

These plants run equipment to breakdown, with maintenance teams fighting fires instead of addressing reliability and operators resisting production stoppages for maintenance. Such failings undoubtedly still exist at too many plants, but fortunately more and more companies are placing greater emphasis on maintenance and seeking outside help to boost the effectiveness of their efforts, as some recent major investment decisions demonstrate.

At the end of last year, for example, Brazilian petrochemical producer Braskem awarded ABB, Wickliffe, Ohio, and Zurich, Switzerland, a $30-million contract to takeover the maintenance of instrumentation as well as rotating and electrical equipment at six plants in Camaçari in the state of Bahia. Under the terms of the two-year renewable contract, ABB will put in a service staff of around 300 to work full-time at the Braskem sites and will earn a variable bonus linked to the reliability of production processes.

Overall, ABB has more than 20,000 people in its service business worldwide — around 20% of its total staffing — accounting for 16% of the group’s revenues. “There is strong demand for our expertise to increase the performance and useful life of plant assets,” says Veli Matti Reinikklal, head of ABB’s Process Automation division.

Moving beyond control

ABB is just one of the many automation companies now benefiting by building up asset management services alongside process control capabilities — in ABB’s case, its PAM (Plant Asset Management) system within the IndustrialIT 800xA control system.

In January, for instance, Emerson Process Management, Austin, Texas, won a $1.7-million contract from Atlantic LNG to monitor the performance of process and mechanical equipment at its liquefied natural gas plant in Point Fortin, Trinidad and Tobago (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Atlantic LNG’s Point Fortin site will monitor over 300 pieces of equipment in four trains. Source: Emerson Process Management.

Atlantic, which is owned by a consortium that includes BP, British Gas and Repsol, will be using Emerson’s AMS Equipment Performance Monitor — part of the AMS Suite of software packages within the PlantWeb digital plant architecture — to monitor more than 340 items of equipment on four trains of the LNG plant.

What packages such as Performance Monitor and AMS Suite in general can do “is give operators insight into the real condition of their assets, give them real-time feedback on the way that they operate the plant impacts asset performance, while at the same time provide the maintenance and reliability teams with additional in-depth tools to focus on predictive diagnostics. We are really redefining the maintenance practices based on predictive tools, as opposed to the traditional approaches to maintaining assets,” says Stuart Harris, vice president of marketing for Emerson’s Asset Optimization business.

Recent enhancements to those Emerson tools include the introduction of advanced diagnostics to the company’s Rosemount 3051S series of pressure, flow and temperature transmitters. This embedded ASP Diagnostics Suite uses HART communications to alert users to abnormal operating conditions through a graphical user interface based on the international Electronic Device Description Language (EDDL) standard that is said to give an intuitive view of the process to both operators and maintenance personnel. The latest version of EDDL also has been incorporated into Emerson’s CSI 9210 Machinery Health transmitter for monitoring motor/pump trains (Figure 2). “The new EDDL interface provides a clearer, visually-intuitive picture of developing cavitation,” says Brian Humes, general manager of the company’s Machinery Health Management business.

Figure 2. EDDL graphics technology gives a clearer picture of equipment status.

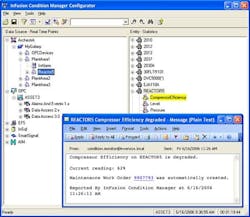

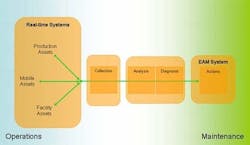

Invensys Process Systems (IPS), Foxboro, Mass., in December 2006, demonstrated its new InFusion Condition Manager software to customers. According to IPS, while other vendors’ condition monitoring (CM) solutions tend to focus on basic monitoring of field devices or rotating equipment, the InFusion offering — building on the company’s field-proven Avantis.CM technology and last year’s introduction of the InFusion enterprise control system — collects, aggregates and analyzes real-time data from a full array of plant assets. “The InFusion Condition Manager can help organizations to move from a reactive to proactive environment in which they can effectively predict and prevent problems before they occur,” says Neil Cooper, general manager of Invensys’ Avantis EAM (enterprise asset management) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Compressor efficiency problem leads to automatic generation of work order.

Honeywell, Phoenix, Ariz., is another major automation vendor taking a broader view of asset management with tools such as its SmartCET corrosion transmitters, which use HART and easily connect to existing distributed control systems (DCSs). Chemicals producer Rohm and Haas has saved more than $500,000 in capital expenditure by using these transmitters to identify the root cause of differences in performance between two identical process units at its Deer Park, Texas, site. “Having a corrosion sensor that connects to the DCS is a real benefit,” says Andrew Wheeler of the Deer Park operations team. “We can view corrosion just like any other process reading and this allows us to make decisions that preserve our equipment.”

Honeywell’s asset management solutions operate through its Experion PKS process control system via a series of software and monitoring products and a single control and maintenance user interface. Products such as Turbo Suite (for rotating machinery), Loop Scout (for control loops) and Field Device Manager are said to take full advantage of the benefits provided by smart field devices in terms of diagnostics and increased reliability. Through its IntelaTrac PKS mobile handheld devices Honeywell also is taking advantage of wireless technology to deliver field data to its Asset Manager system.

The promise of wireless

Most automation vendors appear convinced that wireless is the way forward for better integration between plant CM and the operations side of the business (see "Where is wireless going?"). “There is a tier of assets that operators would like to have information from more frequently, but to date they haven’t been able to justify an online system. Wireless technology is increasingly of interest for those assets. We feel that wireless will open up the potential for additional diagnostics or condition monitoring,” Emerson’s Harris says.

Similarly, Hesh Kagan, IPS’ director of technology for services applications, believes wireless technology will bring “a whole new world of model-based predictive maintenance based on low-end condition monitoring.” Josef Guth, head of the instrumentation business unit of ABB Management Services, agrees: “Increased use of wireless networks will play a key role in the coming years.”

The quality of asset management clearly depends on the quality of the data delivered to the system from the field. However, the quantity also can be an issue. Indeed, sometimes you can have too much of a good thing, warns Jim Henry, Houston-based specialist with SKF, Kulpsville, Pa. “More than a lack of information, companies these days are dealing with an overload of information. They are looking for someone to turn it into knowledge and action.”

Explaining how SKF is transforming itself “from a bearings commodity company to a solutions, knowledge-based engineering one,” Henry says its knowledge of rotating machinery gives the company “a foundation of expertise” in handling those data (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Worker inputs into handheld device as part of reliability improvement program.

“It drives some of the things we’ve built into the [CM] tools we use. We’re focused more on all those assets that aren’t currently covered by a DCS or aren’t online. We help define what is the appropriate level of condition monitoring to be done — from none to something that can be quite extensive — and then help develop the maintenance strategy.”

A limiting factor in extending CM to those assets not equipped with continuous online monitoring is obviously finding, and funding, the staff to collect and analyze performance data. That most assuredly is one area of maintenance that, over the years, has suffered from lack of investment.

Staffing challenges

“It’s a major issue,” says Henry. “Some of the bigger … clients I’ve talked to recently are looking at something like 50%-to-70% staff turnover in the next five years.” Torbjörn Idhammar, partner and vice-president of maintenance management consultant IDCON, Raleigh, N.C., paints a similar picture: “Our surveys show that over three years, the maintenance manager, plant manager and operations manager [of a typical plant] all change — on average, every year one of those three people changes. That’s at the plant level, it’s even more so at the corporate level where there is less understanding of the importance of a maintenance budget.”

The average tenure of a typical plant manager might be only three years but even that short a period can leave a devastating legacy, warns Sue Steele, vice-president of manufacturing and life sciences at contractor CH2M Hill, Spartanburg, S.C. “Someone can run a plant into the ground in that time — squeezing products out by running the plant wide open and ignoring the reliability issue — and still look like a hero, but if they’re not doing any maintenance the new guy has a shambles on his hands and has to spend on equipment improvements.”

Henry acknowledges the pressure on plants to maximize throughput but notes that companies are tackling this by “putting their remaining senior people to work on debottlenecking and throughput improvements — that really require plant-level knowledge and experience — and then backfilling some of the day-to-day asset management work such as CM and vibration analyses — that require more equipment- than plant-specific knowledge — with service contracts from companies like SKF. That’s how some companies are starting to deal with this brain-drain.”

Good vibrations

SKF, in turn, is building its expertise by actively acquiring companies such as Preventive Maintenance Co. Inc. (PMCI), Elk Grove Village, Ill., a firm specializing in vibration data collection and analysis, balancing and alignment, ultrasonics and thermography. “Everybody wants to outsource more and more. A reliability program is huge on the bottom line if done right, but it’s not their core competency,” explains Jim Miller, formerly PMCI president and now SKF’s vice-president of business development, reliability services division. Henry says this was one of the main drivers behind the January acquisition: “What we got was 75 skilled people actively involved in condition monitoring services.”

In a similar move, Emerson recently entered into an alliance with rotating machinery experts RoMaDyn, Minden, Nev., to expand its vibration monitoring service. In addition, the two companies have jointly created a new turbomachinery-diagnostics training course that Emerson is introducing this year.

Highlighting the importance of improving the maintenance skills set, leading CM company GE Energy Bently Nevada, also based in Minden, offers a variety of training courses, including a Reliability Process Workshop, a one-day simulation exercise that rapidly shows how reliability impacts profitability. Bently Nevada, of course, can point to many real-life examples of its CM products in use around the chemical industry — for example, Flowserve Pumps, Dallas, adopted them following a 2005 alliance between the companies.

Meanwhile, in December 2006, Emerson and Mtelligence, San Diego, Calif., formed an alliance aimed more at the enterprise level than the plant. Mtelligence’s software technology will provide an interface between Emerson’s AMS Suite in PlantWeb and enterprise asset management (EAM) systems such as SAP’s Plant Maintenance and IBM’s Maximo. “The Mtelligence relationship makes it easy and straightforward for users to connect the predictive diagnostics from our sort of applications to their EAM or CMMS (computerized maintenance management systems) for the purposes of planning and scheduling. Now you can start to drive those planning and scheduling activities — workload generation and the like — directly off the predictive diagnostics,” says Harris.

Interoperability initiatives

Mtelligence’s interface is built to a relatively new interoperability standard, Open O&M, which is a collaborative venture between the OPC Foundation, Scottsdale, Ariz., Open Applications Group (OAG), Marietta, Ga., and Machinery Information Management Open System Alliance (MIMOSA), Rosemount, Ill., a not-for-profit trade association involved in developing open standards for operations and maintenance. IPS also has committed to the Open O&M initiative by incorporating MIMOSA standards into its InFusion ECS (enterprise control system).

One of the largest developers of OPC software, Matrikon, Edmonton, Alberta, recently released its ProcessMonitor MIMOSA software (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Software now takes advantage of MIMOSA standards.

“Sitting more at the plant historian level,” says Jason Barath, a consultant in Matrikon’s business solutions group, “we don’t deal directly with the plant equipment itself, but it’s very easy to get information from the plant using OPC on the control side. On the business side, MIMOSA is developing the same sort of architecture where you can just drop in plug-ins based on the type of maintenance system you’re using.”

Barath sees a growing interest in these open initiatives: “Condition monitoring has been around forever, but the traditional methods didn’t add real value. But now we have all these real-time systems in place, it’s starting to move. Within the next five-to-10 years we should start to see real growth.”

Given the average three-year tenure of today’s plant and maintenance managers, this might be too far in the future to benefit many of them directly. However, the end result certainly should be more reliable and profitable plants.