Get ready to comply with new security mandates

As part of the Homeland Security Appropriations Act of 2007, Congress directed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to identify and regulate “high-risk chemical facilities.” Specifically, DHS was to require each such facility to conduct a security vulnerability assessment (SVA) and prepare a security plan reflecting risk-based performance standards (RBPS) established by the Department. DHS promulgated the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS) as 6 CFR Part 27 on April 9. CFATS became effective on June 8.

The rule will have widespread consequences because it goes beyond simply regulating chemical plants.

It will impact any facility that handles chemicals on the Chemicals of Interest List (Appendix A of the rule) at levels above the Screening Threshold Quantities (STQ), with a few exemptions stipulated by Congress and practical policy decisions made by DHS. Many of those facilities, should the DHS analyses conclude they pose a high security risk, will be assigned to one of the four tiers. They could represent a wide cross-section of industries and applications that use chemicals. This is consistent with DHS’ role as the agency responsible for the chemicals sector under the National Infrastructure Protection Plan.

This is a very significant development for the chemical sector because up to this point no Federal regulation had defined security expectations for chemical facilities except U.S. Coast Guard Maritime Security Regulations. The Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002 (MTSA) didn’t explicitly define RBPS or tiers. While the MTSA regulations are performance-based for the most part, the Coast Guard does have the authority to specify security measures, whereas DHS isn’t given this authority by the Act.

Under the Act, DHS must establish RBPS for security of high-risk chemical facilities, while industry must perform SVA and develop and implement Site Security Plans (SSP) that address these requirements.

The SSP will need to explain how the site met the RBPS set by DHS. This is a new realm in the world of chemical industry security — so a key aspect of meeting the regulatory requirements will be interpreting these standards and determining the best path to achieving them. No other security regime in the post 9/11 era is attempting to regulate so many diverse types of facilities in such a progressive way.

For some facilities, getting into and maintaining compliance to the rule could require significant investment and operational changes.

Intention of the standards

CFATS was designed to reduce security risk to critical chemical facilities as well as to the communities surrounding them, recognizing that chemicals may be both crucial to other essential parts of society — including public health, the food and water supply, energy and national defense — and hazardous to those working with and around them. For that reason, the regulations will identify chemical facilities as “high-risk” because they have a potential for significant harm to human health and because they are essential to critical missions of the government as well as the national or regional economies. Also recognizing the great variation among facilities that manufacture, store and use chemicals, the regulations are written to be implemented on a site-specific basis, reflecting the security profile of individual facilities.

The new program is:

- Risk-based. CFATS will assign high-risk facilities to one of four tiers and will impose requirements and standards based on the potential risk represented by the particular tier.

- Performance-based. Rather than prescribing specific security measures for all facilities or even for all facilities in a given tier, it establishes RBPS that will allow a facility to implement security measures that, taken together, meet the applicable RBPS for its tier.

- Complementary to existing industry voluntary efforts and investments. Following 9/11, facilities throughout the chemical sector developed security programs and initiatives to reduce vulnerabilities to terrorist attacks. Some companies and facilities implemented their own programs while others participated in broader industry initiatives such as the American Chemistry Council’s Responsible Care Security Code or the American Petroleum Institute’s Security Guidelines. Many facilities conducted vulnerability assessments using methodologies developed by Sandia National Labs, the American Institute of Chemical Engineers’ Center for Chemical Process Safety, or other methodologies derived from those two methods.

While CFATS does build on existing industry efforts, it’s an enforceable regulatory program. Recalcitrant facilities may be fined or even shut down for failure to comply.

The facilities affected

Prescribed screening and evaluation efforts will determine whether a facility is regulated under CFATS.

Chemical facilities that have a minimum STQ of listed chemicals on site will be screened. Subsequent information-gathering and assessment efforts, centered around the SVA, will place regulated facilities into one of four tiers. Each tier will be required to meet RBPS with layered security measures, with rigor increasing with tier. It is believed that the majority of sites screened won’t be included in the regulated community.

Facilities not subject to the regulation include:

- Those exempted by statute, such as facilities regulated pursuant to MTSA, owned or operated by the Department of Defense or the Department of Energy, those subject to regulation by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission; Public Water Systems as defined by Section 1401 of the Safe Drinking Water Act; and Treatment Works as defined in Section 212 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act;

- Facilities that possess or plan to possess listed chemicals but below the STQ;

- Facilities that aren’t considered “high-risk” after DHS screens or further analyzes their activities and potential risks either following submittal of a Top-Screen or SVA;

- Facilities that possess or plan to possess chemicals but whose activities aren’t included in the scope of CFATS by policy (e.g., rail yards were mentioned by DHS in the interim final rule preamble).

The process

CFATS creates a system composed of discrete elements that, taken together, provide a progressive program to identify high-risk chemical facilities and impose security standards commensurate with the security profile of such covered facilities. The DHS-developed-and-owned online process for screening, SVA and SSP submittal is named the Chemical Security Assessment Tool (CSAT) and is available via www.dhs.gov/chemicalsecurity.

Figure 1 describes the general sequence of the key regulatory requirements and milestones. Facilities must first complete a Top-Screen. Those presumed to present a high level of security risk as a result of DHS’s analysis are next required to submit SVA. If the Department then assigns a facility to a tier, that facility becomes responsible for achieving the applicable RBPS and must develop a suitable SSP that DHS validates and approves. Enforcement will be based on the facility’s compliance with it’s SSP

Top-Screen. This collects answers to a series of questions intended to assess different impacts, and levels of impact, that could result from a terrorist incident at the facility — specifically, the risk to public health and safety from:

Figure 1. CFATS involves 10 steps, with more than half involving RBPS. (Click to enlarge)

- in-situ release of toxic, flammable and explosive chemicals;

- theft or diversion of chemical weapons and precursors, weapons of mass effect and Improvised Explosive Device (IED) precursors;

- sabotage or contamination of materials that could release poisonous gases if exposed to water;

- the inability of government to provide critical services, such as supply of potable water and electric power, and safety and security, in the event of an emergency; as well as

- risks to the national or regional economy.

CSAT-SVA. This is a framework for analyzing and managing risks associated with terrorist attacks against critical assets. It provides a simple, convenient, computer-based methodology to identify, analyze and communicate the various characteristics and impacts that may lead terrorists to select a particular target and engage in a specific form of attack. It communicates to DHS the site’s estimate of the security elements currently in place that meet or exceed each of the applicable RBPS related to a common set of threat agents.

The CSAT-SVA has three fundamental objectives:

- Identifying a facility’s critical assets based on the results of the Top-Screen and as directed by DHS;

- Applying specified potential terrorist attack scenarios, as applicable, to each identified critical asset to refine the consequence estimates from the Top-Screen;

- Applying specified potential terrorist attack scenarios, as applicable, to each critical asset in light of the security measures in place to evaluate the gaps between the existing security measures and the RBPS.

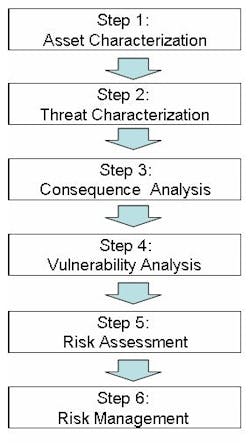

The CSAT-SVA is a six-step process (see Figure 2) that links the output from the Top-Screen and general site attractiveness to specific assets, allowing more-focused consequence analysis and risk assessment, and providing a baseline for security countermeasures that will be articulated in the SSP.

Figure 2. The SCAT-SVA’s six steps lead to an assessment tailored to the site.

It documents the process of identifying security vulnerabilities and provides methods to evaluate the options for addressing those weaknesses using example countermeasures identified in the SSP Security Countermeasure Database.

The CSAT-SVA is used to further characterize the facility, determine plausible worst-case scenarios assuming successful attacks on critical assets, and evaluate vulnerability. A standardized set of potential terrorist attack scenarios and assumptions allows for cross comparison of chemical facilities and the determination of vulnerability on a common scale.

DHS’s presumptive tiering is based on the potential consequences that could be generated following a successful attack or due to the presence of types of chemicals at the facility. (The final threshold values that DHS will use for tier cutoff levels will be classified.) The Department will determine the final tier level for the facility and for the critical assets within the facility based upon the SVA results and the previous Top-Screen information. A facility’s tier level will depend upon the highest tier determined for all of its critical assets.

Potential terrorist attack scenarios

The CSAT tool employs a set of defined potential terrorist attack scenarios, used to both “produce” consequences (for the measurement of criticality) and to measure vulnerability. These aren’t “Design Basis” threats and in no way reflect the type of actual threats against which owner/operators will be expected to “defend.” Instead, they reflect the need for DHS to conduct comparative risk analysis uniformly and consistently across the sector.

The tool does include basic assessments of certain types of threats; however, it isn’t intended to be a full-scope, detailed analysis of all possible areas of vulnerability. It’s a measurement tool that will allow general categorization of a facility as vulnerable or not, critical or not, and, thus, help estimate the degree of risk posed by the listed chemicals. DHS will undertake detailed evaluations of specific security issues as part of the ongoing relationship between itself and the facility owner/operator.

Site security plans

The statute specifies that the Department “shall permit each facility, in developing and implementing Site Security Plans, to select layered security measures that, in combination, appropriately address the Security Vulnerability Assessment [for the facility] and the risk-based performance standards for security for the facility.” The statute specifically prohibits the Department from rejecting a SSP simply because it does not incorporate a specific type of security measure: “The Secretary may not disapprove a Site Security Plan submitted under this section based on the presence or absence of a particular security measure.”

A SSP must take into account both the SVA for the covered facility and the applicable RBPS. The plan must identify and describe the function of the measures the facility will employ to close the gaps between the existing security measures and the RBPS for its assigned tier. DHS will determine that the specific options selected by the site owner/operator protect against the various potential attack scenarios in the SVA and adequately address the RBPS.

Covered facilities also will have a continuing obligation, which will vary based on their risk-based tier, to maintain and periodically update their SSP.

RBPS per tier level

There are four risk-based tiers, ranging from highest risk at Tier 1 to lowest risk at Tier 4. This generally means that Tier 1 facilities must effectively demonstrate “more robust” security systems — meaning those with greater capability, reliability and resistance to defeat than those provided by lower tier facilities. DHS will consistently apply performance standards across all tiers, but guidelines for each tier vary relative to the consequence of malevolent acts posed by each facility. As already noted, the Act restrains DHS from requiring any specific measures.

CFATS includes nineteen risk-based performance standards (see Table 1). Each covered facility must select, develop and implement appropriate risk-based measures to satisfy these standards.

(1) Restrict Area Perimeter. Secure and monitor the perimeter of the facility;

(2) Secure Site Assets. Secure and monitor restricted areas or potentially critical targets within the facility;

(3) Screen and Control Access. Control access to the facility and to restricted areas within the facility by screening and/or inspecting individuals and vehicles as they enter, including:

(i) Measures to deter the unauthorized introduction of dangerous

substances and devices that may facilitate an attack or actions having serious negative consequences for the population surrounding the facility; and

(ii) Measures implementing a regularly updated identification system that checks the identification of facility personnel and other persons seeking access to the facility and that discourages abuse through established disciplinary measures;

(4) Deter, Detect, and Delay. Deter, detect, and delay an attack, creating sufficient time between detection of an attack and the point at which the attack becomes successful, including measures to:

(i) Deter vehicles from penetrating the facility perimeter, gaining unauthorized access to restricted areas or otherwise presenting a hazard to potentially critical targets;

(ii) Deter attacks through visible, professional, well maintained security measures and systems, including security personnel, detection systems, barriers and barricades, and hardened or reduced value targets;

(iii) Detect attacks at early stages, through counter-surveillance, frustration of opportunity to observe potential targets, surveillance and sensing systems, and barriers and barricades; and

(iv) Delay an attack for a sufficient period of time so to allow appropriate response through on-site security response, barriers and barricades, hardened targets, and well-coordinated response planning.

(5) Shipping, Receipt, and Storage. Secure and monitor the shipping, receipt, and storage of hazardous materials for the facility;

(6) Theft and Diversion. Deter theft or diversion of potentially dangerous chemicals;

(7) Sabotage. Deter insider sabotage;

(8) Cyber. Deter cyber sabotage, including by preventing unauthorized onsite or remote access to critical process controls, such as Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, Distributed Control Systems (DCS), Process Control Systems (PCS), Industrial Control Systems (ICS); critical business systems; and other sensitive computerized systems;

(9) Response. Develop and exercise an emergency plan to respond to security incidents internally and with assistance of local law enforcement and first responders;

(10) Monitoring. Maintain effective monitoring, communications and warning systems, including:

(i) Measures designed to ensure that security systems and equipment are in good working order and inspected, tested, calibrated, and otherwise maintained;

(ii) Measures designed to regularly test security systems, note deficiencies, correct for detected deficiencies, and record results so that they are available for inspection by the Department; and

(iii) Measures to allow the facility to promptly identify and respond to security system and equipment failures or malfunctions;

(11) Training. Ensure proper security training, exercises, and drills of facility personnel;

(12) Personnel Surety. Perform appropriate background checks on and ensure appropriate credentials for facility personnel, and as appropriate, for unescorted visitors with access to restricted areas or critical assets, including:

(i) measures designed to verify and validate identity;

(ii) measures designed to check criminal history;

(iii) measures designed to verify and validate legal authorization to work; and

(iv) measures designed to identify people with terrorist ties;

(13) Elevated Threats. Escalate the level of protective measures for periods of elevated threat;

(14) Specific Threats, Vulnerabilities, or Risks. Address specific threats, vulnerabilities or risks identified by the Assistant Secretary for the particular facility at issue;

(15) Reporting of Significant Security Incidents. Report significant security incidents to the Department and to local law enforcement officials;

(16) Significant Security Incidents and Suspicious Activities. Identify, investigate, report, and maintain records of significant security incidents and suspicious activities in or near the site;

(17) Officials and Organization. Establish official(s) and an organization responsible for security and for compliance with these standards;

(18) Records. Maintain appropriate records; and

(19) Address any additional performance standards the Assistant Secretary may specify.

The DHS will issue guidance to assist owners/operators of covered facilities to implement security programs that will meet or exceed the RBPS, thereby providing concomitant levels of security from these threats. This guidance should be available by July 2007, in time for the rollout of CFATS.

The Act dramatically changes DHS’s role from simply advising the chemicals sector to enforcing standards. However, DHS fully intends to continue and even enhance voluntary efforts in the same manner as other regulatory agencies have undertaken advisory, voluntary and compliance programs simultaneously.

National and international implications

CFATS is a unique regulation in that, through a progressive approach of national screening, tiering, vulnerability analysis and performance standards, it defines a risk-based approach to security of the sector. Some may find the process unclear as they try to understand the expectations of the Department in a non-specific performance-based rule. Others will be anxious to understand whether the investments they have made to date in security will suffice. The only way to fully determine that is by going through the complete, sequential process of CFATS, which will take time. Final plan approval only comes after an onsite inspection by the Department.

Inspections, which will be done by Federal inspectors purposely trained and assigned to this duty for higher-tier facilities and third-party inspectors for lower tiers, will introduce a new dimension to security of the sector. Industry undoubtedly is anxious to understand the role that inspectors will have in reviewing plans and conducting onsite visits to verify compliance.

While Congress didn’t mandate consideration of inherently safer technology (see http://www.chemicalprocessing.com/articles/2004/33.html), i.e., approaches that focus on the nature and quantity of materials and their processing conditions, to lower potential consequences, this may become an increasingly popular option. Companies may choose to substitute or reduce to the extent feasible the use of listed chemicals to avoid falling under the regulations or to achieve a lower tier level. This argues that it is a business case to decide the balance between higher standards of security or lower impact of risks.

The most contentious issue at this time is the list of chemicals of interest that DHS proposed to regulate and the associated STQ. Many in industry certainly hope that DHS, in its pursuit of comprehensive national screening and regulation, will find certain applications to be exempt or outside of intended areas of interest when the final list is published in July. Unless the proposed list is significantly shortened, it will snare a vast number of unintended facilities and will have a large impact due to the sheer volume of work required to catalog uses and facts about the substances for the Top-Screen.

No doubt some industries will be surprised to realize the significance of the security measures and associated costs required to achieve the performance demanded by DHS. As stated in the regulatory evaluation associated with the rule, “DHS currently estimates that as many as 50,000 facilities will register and complete a Top-Screen to better define the population of facilities to be covered by the IFR [Interim Final Rule]... DHS’s best estimate, based on currently available information, is that there will be 5,000 high-risk chemical facilities that will be required to comply with requirements of the IFR. Using the point estimate of 5,000 high-risk chemical facilities, the estimated present value cost of this interim final rule is $3.6 billion over the period 2006-2009 (7% discount rate)… Over the period 2006-2015, DHS estimates the present value cost of this interim final rule would be $8.5 billion (7% discount rate).” Of course, the final number of facilities and the security measures and costs required won’t be fully understood until the rule is fully implemented.

These new expenses add to the pressures on U.S. industry, which already must contend with other competing demands for funds and competitive issues in the new global economy. This is part of the new reality of the post 9/11 era — that homeland security consideration is an integral part of every industry, especially if the facilities play an important role in the national infrastructure or could be abused to cause public harm. Other nations have or are adopting similar security requirements, which set new expectations for the sector.

David A. Moore, PE, CSP, is president and CEO of AcuTech Consulting Group, Alexandria, Va. Dorothy Kellogg, MPA, is a senior consultant for the firm. E-mail them at [email protected] and [email protected].