Chemical Regulations: Become Proactive About Compliance

Chemical manufacturers today face increasing and competing demands for compliance. They simultaneously must contend with mandates from regulatory bodies at the national, state and local levels as well as standards and guidelines from industry organizations and international bodies. These dictates span a broad range, including safety, environmental protection, quality and security. They impose a variety of types of obligations — prescriptive, management-based, performance-based, duty and liability, etc. In addition, actions must satisfy corporate edicts, e.g., for productivity, cost reduction and alignment with strategic initiatives.

To meet all these obligations, chemical makers are resorting to multiple programs and systems, which, in turn, incur a significant burden. A conservative estimate of the cost of compliance is 10% of a worker’s time and salary just dealing with regulations. In high-risk sectors, this easily can reach 20%–30% to support dozens of necessary programs. It’s easy to imagine that if the present course continues compliance will require one person to check the work for every person actually doing the work.

Clearly, this isn’t sustainable or desirable. Moreover, for the most part it only addresses the minimum prescriptive elements of regulations and standards.

Yet, the effectiveness of compliance programs for improving outcomes remains a mystery to many companies. These outcomes often are expressed in general terms such as zero incidents, zero fatalities, zero releases, zero defects, zero violations, etc.

Several factors contribute to why companies find compliance effectiveness difficult to measure and, therefore, difficult to improve:

• poorly designed or misunderstood regulatory frameworks;

• absence of defined compliance obligations, outcomes and objectives;

• lack of appropriate models, measures, indicators and controls;

• inadequate management of the effects of uncertainty (i.e., risk);

• a focus on conformance over the achievement of outcomes;

• a prevailing reactive approach based on audits and inspections;

• governance led by predominately lagging indicators and actions; and

• a view of compliance as a necessary evil.

The last factor perhaps is most fatal.

It’s no wonder that many companies struggle to keep up with their compliance, let alone make any real and substantial improvement. It appears that compliance is falling behind and, in the process, may expose organizations to greater and preventable risk.

The Problem

Considering compliance as a necessary evil instead of a necessary good makes companies more likely to take a reactive approach, focusing mostly on non-conformance and with a goal only of passing an audit.

Auditing (and its cousin, inspection) in many ways best characterizes the reactive approach and is the go-to activity for many compliance functions.

Auditing isn’t a new idea. It was first introduced in the financial sector to test the integrity of accounting procedures and financial data. Since then, audit practices have developed alongside changes to standardized accountancy to become a crucial role in governance, risk and compliance activities.

The audit function has evolved beyond financial reporting to cover other compliance programs such as ethics, occupational health and safety, process safety management, environmental protection, quality, security and other compliance objectives. However, there’s an important distinction between auditing financial statements and ensuring compliance outcomes — particularly when they relate to safety, quality and risk. The latter involves preventing what hasn’t yet happened compared to verifying what already has.

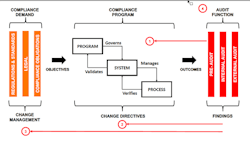

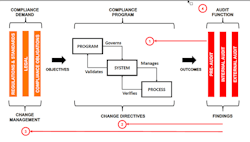

Figure 1. Audits too often serve as the primary tool for compliance.

Not understanding this distinction has resulted in the misapplication of audits as the primary method for implementing, evaluating and improving compliance (Figure 1).

The following are four common misuses of audits applied to compliance programs.

1. Focusing only on activity. To ensure compliance effectiveness, the role of audits is to validate program outcomes and verify the integrity of compliance systems. However, years of auditing prescriptive regulations have created an overemphasis on inspecting activity. This has tempted some auditors to overreach their role by prescribing “how” to achieve compliance even when the regulations or standards don’t specify.

This overreach was rightly stopped in the financial sector with the separation of audit and advisory functions. Unfortunately, this correction hasn’t yet taken hold across many regulatory, standards and certification organizations where these functions often are intertwined.

2. Using findings as requirements. Audits generate findings that, in turn, result in a list of corrective actions. Program managers often use these directly to define compliance obligations. While this makes sense at one level, it poses several problems — particularly when the audit findings inappropriately prescribe remedies.

Those responsible for compliance shouldn’t simply accept findings or an auditor’s particular interpretation without proper consideration of risks, level of compliance maturity and the specific goals of the affected compliance program.

3. Letting findings alone determine needed improvements. Many companies rely solely on audit findings as the driver to improve compliance programs. Audit findings, while necessary to address, on their own aren’t sufficient to drive progress of outcomes because they are too slow to provide feedback and are too late to influence outcomes that have already happened.

Findings also don’t typically cover aspirational or voluntary goals that companies may choose to pursue. Standards along with regulations are, at best, minimum requirements and not intended as the high-water mark. The contention that it’s enough only to do what the law requires is a weak argument, particularly when it involves safety. Indeed, waiting for an injury or an explosion to occur before making safety improvements may be considered unethical, especially when the threats are avoidable.

4. Allowing the audit function to assume managerial accountability. The lack of clear accountability for compliance obligations often results in the audit function taking on the role for determining what the obligations should be and how they should be met. This is inappropriate because it diminishes the responsibility of managers who are the ones who should be accountable. Compliance responsibility is a managerial role not that of an auditor or committee.

Absence of accountability often is indicated by the presence of excessive audits such as pre-audits to get ready for internal audits to get ready for external audits — all of these in hopes of satisfying an uncertain benchmark defined by someone else.

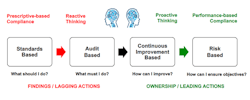

Figure 2. Performance and outcomes have become more important.

The Solution

Compliance obligations have evolved in response to the progression of design frameworks, specifically those focused on performance and outcomes (Figure 2). This demands a proactive approach.

Fundamentally, the purpose of compliance hasn’t changed and remains centered on reducing risk. Now, however, programs must actively manage risk to ensure achieving the outcomes of compliance instead of only addressing prescriptive requirements.

Each compliance program does this by managing the risks associated with the uncertainty specific to safety, quality, security and other impact categories.

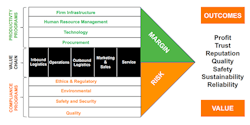

A significant and serious critique with respect to compliance is that conforming to a standard or regulation doesn’t necessarily lead to achieving the anticipated outcomes. This is one of the reasons why industry has been moving toward a holistic and integrated approach across all the compliance functions (Figure 3). Simply conforming to prescription no longer is enough. The need to be effective has become the new normal for compliance.

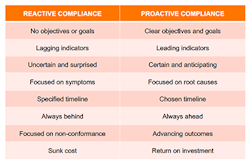

With the changes to the compliance landscape, chemical makers today must become proactive — seeing compliance as a necessary good rather than as a necessary evil. Table 1 contrasts proactive and reactive approaches.

Proactivity is more than an attitude or a bias. It is itself a process of action that includes anticipating, planning and striving to create a future outcome that has an impact. This is precisely what’s needed when the goal is to improve outcomes.

Figure 3. The trend is toward a more-holistic and proactive approach.

So, let’s look at proactive strategies to address the four misuses of audits:

1. Take ownership of all obligations. This means more than simply complying with a given regulation, standard or guideline. Ownership means being responsible and answerable for the outcomes of compliance obligations, which fundamentally are the promises companies make to stakeholders.

I recommend the following steps to clarify compliance obligations and increase the likelihood of achieving them:

• document the context and expectations for each obligation;

• define what constitutes evidence of compliance;

• specify how progress against outcomes will be measured;

• spell out what standard will be used to establish normative processes;

• identify what is needed (structure, resources, technology, culture, etc.) by the organization to attain the desired outcomes; and

• detail and evaluate risks (both threats and opportunities) for each obligation.

2. Embed compliance within the organization. Compliance requirements manifest themselves inside a business in many ways. However, two contexts address the majority of an organization’s compliance obligations:

• management systems, e.g., safety, environmental protection, risk management, quality, audit, project management and others; and

• processes under regulation, such as human resources, security, finance, engineering, operations, maintenance, supplier management, etc.

Compliance benefits from being directly embedded into each process rather than left only to audits and inspections. This provides an ongoing perspective rather than after-the-fact results reported by an audit. With this in mind, adopt some important metrics:

• measures of effectiveness that assess progress towards compliance outcomes, as well as measures of effort;

• measures of compliance that provide evidence of compliance and key results critical to compliance; and

• measures of performance that relate to the operations of the compliance program, systems and processes, as well as measures of capability.

3. Monitor the status of your compliance in real time. Regulatory and standards organizations want to know whether companies have met their compliance obligations in the past but, more importantly, that they can meet their compliance obligations in the future. The latter is a measure of resilience, which is critical for companies operating in highly regulated, high-risk sectors.

Chemical makers should establish real-time monitoring so they always are certain of their level of and capacity to attain compliance.

Achieving and staying in compliance all the time actually takes less effort. The situation resembles that of trying to lose weight. It’s easier to keep the weight off rather than to gain and lose it time after time. In addition, and what’s often overlooked, is that keeping the weight off gives you the benefits of a healthier lifestyle all the time. You will have the energy to do the things that really matter and are important to you. The same is true for compliance — don’t wait for an audit when you can experience the benefits of always being in compliance!

Perhaps the reason that companies do wait is that they are caught in the reactive audit-fix cycle that, even if they double down, only will reinforce the very reactive behavior from which they are trying to escape.

4. Use continuous improvement to break the reactive cycle. “Lean” has taught us that improvements done in an incremental and continuous fashion can add up to substantial benefits that accrue over time. It’s not surprising that many standards now require continuous improvement and have adopted the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle first introduced by Deming and central to Lean.

However, to avoid investing too much or too little, constrain improvements to those that foster desired outcomes. Improvement cycles also must be careful to mitigate risks introduced either in implementing changes or by a change itself. This requires a risk-based change process that’s seldom found with Lean improvements but that’s critical for advancing safety, environmental protection, quality and security objectives.

Table 1. Proactive compliance can provide better performance and outcomes.

Become Proactive

For many years compliance has been based on a reactive model that, for the most part, addressed conformance to prescriptive requirements. Unfortunately, this has reinforced reactive behaviors that now work against achieving the intended outcomes needed to support recent and anticipated changes in regulations and industry standards.

Companies that continue to implement compliance programs using a reactive model are at risk — with the most significant risk the lack of proactivity necessary to address changes introduced by outcome-based compliance.

As compliance requirements continue to change from prescription to outcome-based designs, continuous improvement and adoption of risk-based strategies will gain greater emphasis. These changes more than encourage proactive behavior — they require it!

Chemical makers that adopt a proactive approach will implement processes characterized by anticipation, planning, and striving to create a future outcome that has an impact. These companies will find that they no longer wait for an injury or an explosion to occur, audit findings to be released, or issues to mount before they act. As a result, they will experience reduced risk, make greater progress towards compliance outcomes, and gain increased trust from their stakeholders.

RAIMUND LAQUA is founder and chief compliance engineer of Lean Compliance Consulting, Dundas, Ont., Canada. Email him at [email protected].