Many projects suffer because needed capital assets aren't delivered "on time" and "on budget." Such mishaps take a toll on corporate profitability as well as a company's ability to service existing customers or seize market opportunities.

Effective project controls should minimize, if not eliminate, such capital asset issues. It's the job of project controls personnel to provide a sound and functional hammer with which the project manager can build a successful project.

However, many managers complain that project controls haven't achieved expected results. Too often, efforts don't pan out because of inadequate attention to the "people factor." Success requires employing staff with the right skill sets and experience for their roles, and providing organizational and functional environments that allow them to work effectively.

In many instances, you can significantly improve project controls' effectiveness simply by taking steps to identify and remove those issues that prevent its practitioners from doing their work. So, here, we'll look at ways to tackle the people issues. We'll focus on strategies that can maximize the people side of the project controls equation and enhance overall capital-project performance.

THE PROJECT TEAM

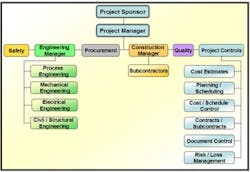

Let's start by defining the roles of a few of the many members of a typical project team (see Figure 1).

The project manager is responsible for coordinating all participants in a capital project. This person should have organizational skills, teambuilding know-how and project execution experience. A project manager motivates, guides and facilitates the outcome of a project. So, the person must be adept at seeing what must be done, deciding who must do it, and ensuring it gets done.

The project engineer expedites the flow of information among disciplines, such as design, environmental health and safety, and procurement, as well as vendors, fabricators, construction managers, contractors, and commissioning and startup personnel. A project engineer facilitates technical resolutions and keeps the technical wheels turning -- allowing the project manager to focus on client, business and commercial issues.

Discipline supervisory staff oversee execution of the work in their field of expertise, ensuring individual workers perform their tasks in a satisfactory manner.

Project controls personnel provide cost- and schedule-performance feedback to all the above team members. They look for problems; investigate, document and quantify them; and bring them to the early attention of the project manager, project engineer and discipline supervisors. The team then can form a consensus on the cause and potential impact of each problem and the appropriate actions to take.

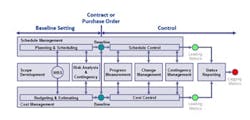

The project controls discipline is charged with defining, quantifying and tracking all cost and schedule issues. It provides the subject matter experts and experience for executing work related to:

• estimating;

• risk assessment;

• planning and scheduling;

• cost management and forecasting;

• progress and productivity measurement;

• trending and change management;

• contingency management; and

• project metrics' capture and close-out.

Figure 2 shows how these activities fit into the total project-controls process.

IMPROVING PROJECT CONTROLS

Appropriate steps to enhance effectiveness depend on the company and how it organizes its project controls. However, in all cases, they involve systematically removing the root causes of the problems generating inefficiencies.

So, let's discuss approaches that can eliminate specific obstacles to the functionality and effectiveness of people charged with carrying out your project controls initiatives.

Organizational issues:

1. The position of project controls in the corporate organization chart often stands in the way of effective performance.

Project controls personnel work intimately with project managers and deal with data that potentially may indicate positive or negative trends. Therefore, the relationship of project controls in the overall corporate structure must facilitate unbiased reporting of trends to corporate management. (See Figure 3.)

2. The structure of the project controls organization doesn't provide for adequate management support of project controls staff assigned to individual projects.

Project controls specialists on all projects must have sufficient departmental support. These specialists shouldn't be charged with fighting the philosophical battles that sometimes occur with project team members when deciding, for example, what needs to be said (or not said) in corporate reports. When such a problem surfaces, an individual specialist should be able to get his or her manager to promptly intervene and resolve the dispute.

Human resource and personnel utilization issues:

1. Attrition rates of project controls personnel often exceed the rate at which they can be replaced by new hires.

Companies must implement programs to evaluate factors causing qualified project controls people to leave. Exploring this more during exit interviews can help, although it's after the fact. A better technique is to explicitly evaluate job satisfaction during annual performance and salary reviews; additional, mid-year reviews can provide early warnings of potential problems. Many factors can contribute to higher attrition rates, so it's important to pin down the drivers at a particular location to determine the most effective actions.

2. Sufficiently seasoned project controls personnel are becoming a scarce commodity, and are difficult to locate and hire.

Human resource and managerial staff must investigate how better to locate potential resources. Steps may include: maintaining contacts in professional societies (AACEI, PMI, CII, etc.); listing job openings in their periodical publications and on their websites; posting positions available and checking resumes not only on general Internet job boards (e.g., Monster.com and CareerBuilder), but also on project-controls-specific websites (e.g., Schedulers.com); making concerted efforts to identify and utilize project-controls-specific employment personnel services; and using outsourced personnel providers that specialize in project controls resources.

3. Project controls positions in many organizations offer a limited career-development path, resulting in talented personnel leaving after a short while for "greener pastures."

This effectively guarantees a shortage of experienced personnel in the long term. Companies must devise strategies to retain highly skilled people by providing avenues with increasing responsibilities and appropriate compensation levels. Many approaches are available -- the trick is finding one that's right for your organization.

4. Project controls personnel aren't sufficiently integrated into the project. All too often, they're only peripherally involved. This sometimes stems from resource restraints that limit hiring and thus spread personnel across too many projects.

Remember, reports preparation is only one of a project control specialist's activities. To avoid becoming marginalized, the person must interact with the project team outside of the reporting environment. Otherwise, the data and analyses produced won't relate to what's actually occurring. The numbers are only one basis for analysis. Effective communication of ideas, opinions and concerns also is necessary. Improper integration makes project controls appear as more of an audit than a project-support function. Such a perception can get in the way of the proactive (rather than reactive) role that project controls should play.

5. Project controls work is considered clerical.

The work is as technical as any other on the project. By its very nature, it requires intuition, creative problem-solving, individual initiative, technical knowledge and independent analytical skills. Additionally, project controls specialists must know how to manage relationships, including those needed to elicit information from various sources as well as to confidently present and argue positions to all levels of project and corporate management.

Treating these people like clerks can reduce their involvement to the point where it's totally ineffective, and leads to compensation that makes it impossible to hire the right people to do the job. You wouldn't pay a process safety specialist a wage appropriate for a non-skilled laborer. Don't make such a mistake in project controls.

6. The skill sets of project controls personnel don't align with their job descriptions.

Project controls encompass many discipline knowledge areas. Job duties must match the skill sets of its practitioners. For example, it's difficult to find large numbers of staff proficient, say, in both cost and scheduling analysis. You may have a person who's skilled in one area but who only has a rather basic understanding of the other. People naturally focus on the areas where they feel most confident, putting lower priority on those areas where they feel most uncomfortable and limited. So, avoid assigning tasks outside of someone's proficiency. In this case, it would be better to use a separate scheduler and cost engineer, allowing either the most experienced project controls specialist or the project manager to take the lead role in coordinating their work.

7. Project controls personnel aren't trained specialists in their discipline but are simply drawn from other areas of the company.

A project controls organization must include an adequate level of experienced practitioners. Otherwise, the work will be ineffectively executed. And it will be impossible to provide the leadership and mentoring required to train new people in the skills and techniques required.

AVOID COMMON ERRORS

A number of lapses and miscues frequently undermine the prospects for success:

Well-organized "what-to" and "how-to" guides are scarce or nonexistent. Often, you can rectify failures in performance simply by providing appropriate procedures, work practices, guidelines, etc. A practitioner must clearly understand what he or she is being asked to do. Procedures sometimes are written at too high a level to help the worker actually charged with carrying them out. Correctly written instructions significantly decrease the learning curve for new employees and don't allow supporting groups to dodge their responsibilities.

The impact of too much change is under-estimated. In considering system changes, retain as much as possible things that already work or that can be made to work with only minor "tweaking." Don't make massive changes for only incremental benefits. Familiarity with parts of a process goes a long way to fostering a willingness to work with the parts that are new. The changeover then can be viewed by participants simply as an integration effort rather than a replacement. It's a psychological advantage that shouldn't be under-estimated.

Systems fail to address ease of use in "production mode." Always strive to design new or revised systems to allow users to execute complex commands in simple repeatable ways. For example, if ten reports are printed every month, a user shouldn't have to waste time printing each, but should be able to click a couple of buttons to select and initiate the printing of one, or some, or all of them.

People actually doing the work don't clearly understand who is responsible for what in a given process. Confusion often arises not simply from imprecise definitions in job descriptions but from lack of forethought regarding the details of how a process works. So, clearly define roles and responsibilities in job descriptions, procedures and work practices. You also must carefully think through both the detailed methods and formats to be used in transmitting data among participants, as well as the amount of time realistically required to produce or transmit the data needed.

Procedures are way too high level and obscure in nature, contain more philosophy than content, and rely on a lot of "motherhood" in their description of the work. Mandate that procedures define who does what, in terms of actions and deliverables (such as specific forms, reports, etc.), not just functions to be performed. This includes transmittals, approval, sign-offs, etc. Procedures and work practices must offer clear direction and instructions -- and leave no question about what must be done and how to do it.

Systems and procedures incorporate weaknesses that could have been avoided by tapping the knowledge and experience of people at the working level. Don't let managers design systems on their own. Managers understand needs and strategies, but require input from subordinates who do the work to design systems that actually will work.

Systems are implemented on all projects at once. Too much change causes too much confusion, and everything can fail because of it. Pilot-test production systems or subsystems on no more than a handful of projects first. Trying to deal with masses of data involved in all your projects usually is unmanageable, especially if you find the initial rollout requires design modifications to be made. Why would you want to change the coding, say, for thousands of records on 100 projects when you could have discovered (and fixed) the problem on only one? There's nothing like working with real project data to help you identify the types of "bugs" that might occur in the theoretical design. Gain confidence first and then gear up to migrate all your data.

ACHIEVE BETTER RESULTS

The efficient production of project controls reports isn't the "do all" and "end all" of effective project management. Indeed, how project and corporate management use the data and trends in these reports can make-or-break positive outcomes. So, don't overlook this aspect in evaluating the effectiveness of how projects are managed.

However, shortfalls in the project controls organization itself can severely undermine effective project management. Some sensible strategies can go a long way toward correcting deficiencies and thus improving capital performance.

ROBERT MATHIAS is an executive associate at Pathfinder, LLC, Cherry Hill, NJ. Email him at [email protected].