Tame Your Transient Operations

A disproportionate percentage of process safety incidents have occurred during transient operations, which include those conducted infrequently such as startups or shutdowns as well as abnormal or emergency events. A typical refining or petrochemical facility will spend less than 10% of its time in transient operations — yet 50+% of process safety incidents occur during these operations (Figure 1) [1–3]. Deficiencies in procedures and employee training often are cited as root causes of these incidents. The increased reliability and extended turnaround intervals of plants result in less familiarity with tasks outside of normal operations. So, while it's critically important to follow procedures during transient operations, a high percentage of procedural violations are found to occur during them.

Here we present a Hazard and Operability (HAZOP) methodology designed to verify that hazards of transient operations are identified and adequately controlled. This approach already has proven its value at ExxonMobil sites.

Types of Transient Operations

The HAZOP process must consider two categories of operations that have potential for an acute loss of containment, resulting in a higher consequence incident:

1. Non-routine operations or planned operations that infrequently occur. Such events include: startup of a major unit, including startup from total shutdown; shutdown or startup of major equipment within a process; operating with a non-standard equipment configuration on a unit, such as a major pump or compressor out of service, inventory shortages or excesses, boiler unavailable, and non-routine testing of a critical device with potential to shut down a unit; and unique or unusual feedstock or grade changes (throughput or quality).

2. Abnormal or unplanned operations. Examples include: operations outside of equipment's design specifications; those past the point where routine corrective actions will work, e.g., reactor runaway; unplanned abnormal equipment configuration; unscheduled unit shutdown; emergency operator actions, including responses to "SHE [safety, health, environmental] critical" alarms; and a loss-of-containment event.

Transient operations may include catalyst change-out or regeneration, decoking, fired heater lighting or other non-routine or abnormal chores.

A common element in transient operations is the requirement for increased human interaction with the process. Often the operator and procedural controls are the key layer of protection for preventing an incident. Reduced operator experience — because of retirements, longer turnaround intervals, and more reliable units — frequently results in more reliance on procedures as a source of information and a critical layer of protection against process hazards.

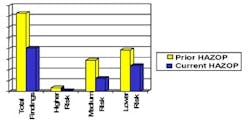

In the United States, OSHA 1910.119, "Process Safety Management of Highly Hazardous Chemicals," requires that an initial process hazard analysis (PHA) completed on a covered process be updated and revalidated at least once every five years [4]. Given a sound management of change (MOC) system to identify, evaluate and ensure the adequacy of controls managing risks associated with the newly introduced hazards, historically a significant reduction in HAZOP findings occurs after two to three cycles of a traditional "redo" HAZOP/PHA. Figure 2 illustrates an example of these diminishing returns.

A Different Focus

The Transient Operation Procedural Focused HAZOP (or Transient Operation HAZOP for short) differs from a conventional HAZOP. It focuses on operational tasks and procedural controls, which are believed to yield greater returns, specifically in the third or later cycle of a more traditionally focused HAZOP.

The Transient Operation HAZOP (TOH) process centers on identification of required unit-specific activities (tasks) with a potential for an acute loss of containment and an in-depth review of the procedural controls necessary for safe and successful completion of those tasks. Timely identification of hazards, adequacy of procedural and design controls to ensure correct sequencing, early feedback of potential errors, clarity and completeness of transient operations all are carefully assessed. The technique uses a combination of knowledge and experience of a cross-functional team, guide words and reference lists to drive a disciplined approach to identify and suggest enhancements for procedural and design-related issues.

The TOH process offers manufacturing sites a number of potential benefits:

• an in-depth fresh look at "higher risk" transient operations requiring human intervention where procedural controls are used to manage residual risk;

• more-complete and easier-to-follow procedures where procedural controls are key to safe operations during the transient condition/phase or state of the process;

• increased operator awareness of hazards, design controls and potential consequences of not understanding the operation and procedural controls of a transient condition;

• greater consistency in procedural controls as well as potential identification of needed additional design controls for transient process conditions; and

• experience in applying procedural controls that can be applied beyond transient operations.

The TOH approach can provide stand-alone analysis prior to a planned transient operation. It also can be used in conjunction with a traditional HAZOP based on mechanical flow diagrams (MFDs) or piping and instrumentation diagrams (P&IDs). Finally, it can support revalidation of an MFD- or P&ID-based HAZOP/PHA for units needing revalidation.

The Approach

The TOH method involves several distinct steps.

Team formation. The team's composition and experience requirements are the same as for an MFD- or P&ID-based HAZOP with the following exceptions:

The leader should be trained in the TOH process and should have participated in a TOH run by a qualified leader. This person is responsible for facilitating the work process and producing the final report.

The operations (process) representative(s) should be qualified in both field and control console operations, and be intimately familiar with the tasks being reviewed — particularly how they actually are completed in the field. While one person with adequate experience in both areas would suffice, having a second operations representative (preferably from a different shift) likely will add substantial depth and breadth. We recommend having two operations representatives. The operations representative(s) walks the team through the details of transient operations under review and may be assigned to capture "redlined" changes to procedures.

The process design/technology representative must know the type of process and equipment being studied as well as the company's design standards and practices. This helps in communicating design intent of the equipment. The process design/technology representative is responsible for following the operation under review on the MFDs or P&IDs.

Unit startup, shutdown, emergency operator intervention and other transient activities often involve flaring, thermal oxidizers, scrubbing systems, generation of more or different waste streams, etc. As a result, part-time support from an environmental engineer will provide value and typically is justified.

Pre-selection of unit activities and related procedures. The leader, operations representative(s), and process design/technology representative should conduct a first-pass screening of all required unit activities and related procedures to identify those that meet the criterion of a "higher risk" transient operation. This will streamline subsequent review and ensure consistent application of the HAZOP technique.

Assembly of reference documentation. The team must have access to the same information that's required for a traditional HAZOP study, including: material safety data sheets (MSDSs), simplified flow diagrams, detailed MFDs or P&IDs, electrical area classification drawings, pipe specifications, facilities siting studies, unit operations, maintenance, and emergency procedures, reports of incidents that occurred on the unit, and a list of employee concerns.

Solicit comments and concerns from employees and affected contractors — involve the first line supervisor and other line management in the communication process. Focus on potential loss of containment and human factors issues. Place special emphasis on the experience of operators during abnormal and non-routine operation but consider all concerns during the HAZOP process.

Final selection of unit activities and related procedures for review. This is the full team's responsibility. During its initial meeting provide a "HAZOP Kick-off Summary" to introduce the team to the TOH's purpose, scope and methodology. After the kick-off, the entire team should look over all incident report summaries assembled for the unit under review. Focus on process safety and environmental incidents and near misses. Review in detail reports on incidents that involve transient operations with an actual or potential release of hazardous materials to identify operations to include in the scope of the review. Next, the team should assess all identified employee concerns, to determine operations and related procedures with which employees may have issues. Carefully consider this information when selecting the operations and tasks to include in the scope of the review. Finally, the team leader and process design/technology representative should inquire about higher-risk unit activities and practices that may not be documented. Capture findings where procedures or adequate procedural controls aren't in place on the HAZOP worksheet as follow-up items and risk-assess them, with potential improvements documented for consideration.

The entire team should review the first-pass screening of all documented unit activities and related procedures to be included in the study. Team discussions then can lead to adding or removing items from the list.

| Guide Word | Meaning/Explanation |

| Who | Is it clear who and how many individuals are needed to perform the step? Have minimum staffing levels for this sequence been established, documented and communicated? This is particularly important for field/console interaction issues. It may be obvious for the more experienced and knowledgeable individuals, but is it appropriate for the "average" operator? |

| What | Is the broad objective stated for the series of steps? This allows the people involved to adapt to changes that might be happening versus what the procedure writer experienced before or expects. This is where the team picks up missing steps, actions and unanticipated situations — for example, nitrogen purge of a large flare line isn't called out before commissioning. |

| When | Is the timing or order of the task important? This comes into play if related parts of the unit are being operated on by different crews — for example, one crew commissions the flare line and another is pressuring up equipment. |

| How Long | Is the duration or length of time for an action, e.g., purging or agitation, to continue important? |

Conducting procedural review. The leader should orient team members lacking training in the TOH approach. Often this means explaining the guide word sheets and discussing examples (see Table 1). Review each guide word and corresponding explanations. Typically this activity requires about 30 minutes. The 20 guide words serve as memory joggers to bring out the knowledge and experience of the team. The TOH methodology uses this knowledge and experience as well as documented procedures to guide the team through the unit and facilitate identification of hazards.

The operations representative(s) should go over with the entire team a summary of required operational activities (tasks) associated with the specific transient operation. The review should use unit MFDs, P&IDs and procedural sequence flow diagrams, as appropriate, to assist the team in its understanding. Typically a second member of the team (usually the process design/technology representative) will follow the operation under review on the MFDs or P&IDs. Discuss any potential procedural or equipment-related questions as they are identified.

The team should gain an understanding of required operator actions, hazards and potential higher-consequence loss-of-containment risks associated with the operation, and all preventing, alerting and mitigating controls in place. The team should test to ensure that procedures have been developed and are up-to-date for the transient operation under review, personnel responsible for conducting the operation have been adequately trained, and risks have been adequately controlled through application of hardware and procedural controls.

The team initially should scan the procedure as a whole, looking for items contrary to good format, e.g., use of warnings, cautions and notes, sequencing of activities, confirmation that steps begin with action verbs, etc. Group deficiencies, as applicable, and note them as finding(s) for the individual procedure.

Next, the team should break every procedure into a sequence of related steps. For each sequence, ask the question, "Will a deficiency in this sequence of actions potentially lead to a higher-consequence out¬come?"

If there is no potential, mark that set of steps in the right or left margin vertically with a highlighter to document the section has been reviewed.

If a risk exists, evaluate each step separately. Start by asking: "Will a deficiency in this step potentially lead to a higher consequence outcome?" If the answer is "no," move on to the next step. If the response is "yes," evaluate the step using the knowledge and experience of the team, aided, as necessary, by guide words. The evaluation should identify ways to improve the procedure to reduce the potential for an incident to a very low probability.

Determine if a procedural control is the most effective means to ensure activities are safely and reliably conducted. Improvements may be a change in wording, addition of a caution or warning box, or even additional facilities or controls to mitigate the risk. Document findings as a redlined change to the procedure or as a follow-up item on the HAZOP worksheet. It's best to use a computer projector to display the current procedure and the recommended change to the full team. Finally, highlight in the margin each line of the steps evaluated to indicate it was discussed in detail.

Subject any place in a procedure with an existing caution or a warning box to a more detailed evaluation. Confirm or add a caution or warning box, as appropriate, for the potential consequence. Check each precautionary statement to ensure it:

• alerts the operator to the hazard;

• includes a description of the necessary actions to avoid the hazard; and

• details the potential consequences of ignoring the warning.

Once the entire procedure is reviewed, repeat the review steps for the next procedure until all chosen for review are complete.

Documentation of findings. Capture follow-up items as redlined revisions to the procedure — if a change is simple, well understood and can be addressed by the team's suggested wording. Note on the master review copy of the procedure follow-up items that can't be addressed by a simple rewording with an item identifier, just as is done to drawings in redo HAZOPs (e.g., S-1, E-2, O-3).

Indicate on the HAZOP worksheet each finding identified for further consideration as a follow-up item. If the team can't achieve consensus on procedural controls or any improvements to those controls, it may consider enhanced training, process automation tools or facility changes to reduce the risk. Risk-assess any findings that call for facility changes and prioritize them for follow-up. Document recommended additional controls.

Unit tour. Conduct a screening-level walk through the unit, to spot-check effectiveness of SHE-related management systems and to identify SHE hazards and operational issues not previously pinpointed by the team. Such a tour typically takes 2–4 hr. During this phase, the team must:

1. Test supporting systems in place to ensure transient operations are completed in a safe and effective manner;

2. Scan the unit for general process safety issues within the scope of the review; and

3. Identify any potential human factors issues that could potentially contribute to a significant consequence event. Check features such as:

• labeling of important equipment and lines;

• location of crucial valves;

• arrangement of valves that need to be operated in critical sequences;

• placement of manual control valves and their associated local meters;

• whether equipment and lines can be located and safely isolated during an emergency; and

• whether environmental factors, such as visibility and access, have been adequately addressed in the design.

It may be preferable to schedule this tour later in the study, to better assess issues identified as a part of the procedure review. The team should consider any issue with potential to contribute to release of a highly hazardous material as a finding.

Documentation. The reporting phase of the TOH process involves documenting the scope of the review, team composition, documentation reviewed, redlined copies of all procedures reviewed, as appropriate, identified follow-up items and associated risk assessment, as applicable. Include following lists in the final documentation of the completed HAZOP:

• team members, responsibilities and years of experience;

• procedures reviewed;

• incident investigations scrutinized; and

• other documentation examined, as appropriate — e.g., summary of MOC metric data, facility siting studies, process flow diagrams, P&IDs, MSDSs, electrical area classification drawings, safety relief review studies, and SHE critical equipment lists.

Successful Use

ExxonMobil has rolled out the TOH method at refining and chemicals manufacturing operations worldwide. More than 90% of manufacturing sites globally have finished initial TOH application. The TOHs completed to date are identifying findings of significance and providing value to the business. In addition to recommended procedural controls, application of the TOH methodology has determined the need for, and recommended, potential additional hardware and software hazard controls. The TOH methodology truly is more than just a procedures review.

ExxonMobil Refining and Supply and Chemical Companies have systematized the application of the TOH methodology through their global manufacturing operations integrity management system practice, ensuring a unit HAZOP specifically focused on transient operations is completed after the second HAZOP cycle. Additionally, global reliability system elements include milestone-driven application of the TOH methodology during turnaround planning and specific abnormal and non-routine operations.

In late 2008 approximately 1,200 findings from 27 completed TOH studies were analyzed for common findings, with the learnings then captured and communicated, as appropriate, through the organization. The ultimate goal is to enhance organizational knowledge so risks associated with process hazards can be consistently controlled to acceptable levels across the business.

A Valuable Tool

The TOH methodology can serve as a powerful supplement to traditional HAZOPs. Its focus on infrequently performed operations that require an increased level of human interaction with the process addresses situations that generate 50+% of medium- and higher-risk process safety incidents. The outcome is more-complete and easier-to-follow procedures for managing the process through transient states; increased operator awareness of hazards, design controls and the potential consequences of mal-operation; and experience in applying procedural controls that can be applied beyond those procedures covered in the TOH process.

Scott W. Ostrowski and Kelly M. Keim are process safety engineering associates for ExxonMobil Chemical Co., Baytown, Texas. E-mail them at [email protected] and [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Duguid, I. M., "Analysis of Past Incidents in the Oil, Chemical and Petrochemical Industries," Loss Prevention Bulletin, No. 142, p. 3, Institution of Chemical Engineers, Rugby, U.K. (1998).

2. Duguid, I. M., "Analysis of Past Incidents in the Oil, Chemical and Petrochemical Industries," Loss Prevention Bulletin, No. 143, p. 3, Institution of Chemical Engineers, Rugby, U.K. (1998).

3. Duguid, I. M., "Analysis of Past Incidents in the Oil, Chemical and Petrochemical Industries," Loss Prevention Bulletin, No. 144, p. 26, Institution of Chemical Engineers, Rugby, U.K. (1998).

4. "Process Safety Management of Highly Hazardous Chemicals," 29 C.F.R. § 1910.119(e)(6), U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Washington, D.C. (2008).