Pacify the Fear of a Changing Work Environment

Management of Change (MOC) has been one of the hardest of the PSM requirements for industry to master. When we analyzed MOC failures we discovered it isn’t technical incompetence. So, what is the root cause for such failures? It’s the time involved by key personnel in processing multiple changes and their effects combined with juggling other duties. What is missing is an appreciation for how change affects the workflow of operators and managers. We have seen examples of these problems in several familiar industrial accidents including Flixborough, Union Carbide’s Bhopal, BP’s Texas City, ExxonMobil’s Longford and Texaco’s Pembroke.

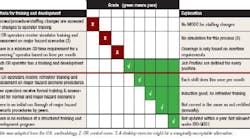

This is an important piece of information if we consider that very few companies apply Management of Organizational Change (MOOC) procedures. A brief review of industrial accidents is all that is needed to show how important it is manage the human element during process changes. The companies that are doing MOOC are doing it in the same spirit as MOC; we often see a superficial discussion of a badly conceived plan. The best we’ve seen is a human factors checklist (Figure 1) from the Chemical Manufacturer’s Association (CMA), “CMA Management of Safety and Health During Organizational Change - A Resource and Tool Kit for Organizations Facing Change.”

Figure 1. Splitting an operator between field and control room could have consequences.

The checklist is intended as a motivational tool. There is more to an MOOC review than the checklist. As a credit to the CMA, they defined how a multi-disciplined team should review and understand a change and it’s implications. One fly in the ointment is that like a PHA review, the value of a MOOC study relies on the quality of the team searching out potential problems and its preparation prior to the discussion. Often such a review would benefit from a “gap analysis” to ensure that the new organization fulfills the needs of the people living within its structure and the goals of the company. This goes well beyond the “Yes” and “No” of a generic checklist.

I recently reviewed one of these completed checklists at a major U.S. refinery. The team could say “Yes” to most of the questions but they never debated the subject. If they had done so they would have discovered that the existing training was inadequate. The only reason that the operators are competent is that, after 20 years on the job, they had found their own ways to get the job done. Contrary to company policy, procedures weren’t documented, validated or tested. On one of those rare occasions when the holes in the Swiss cheese line up and an accident occurred operators were condemned by managers who didn’t understand the process the way the operators did.

The failure of this method shouldn’t surprise anyone in the chemicals industry. During the evolution of the PHA some companies tried to automate the process by using checklists. It was a rude awakening when they discovered that the HAZOP was a better approach — compelling engineers to consider integration of their design into a plant system. A formal HAZOP has its own checklist, a list of guidewords asking, for example, “Is the temperature too high, or too low?” The power of the guidewords is that they provoke a debate: What could cause the temperature to be too low? Is the cause significant — could someone be hurt or would equipment be damaged?

In practice

Now, let’s consider how a human factor checklist would be used in practice (Table 1).

Table 1. In this example training gets a 'D' because no MOOC plan exists and there is no simulator training. (Click to enlarge.)

Suppose an organization that has roaming operators that work inside and outside of a control room. Half of their day involves working in the field and the other half with a distributed control system (DCS). The organization plans to change this. In the new structure operators are to be dedicated exclusively to inside work.

After a cursory review managers recognize that the current DCS workload represents only about 40% of a shift’s workload. The easy solution is to consolidate this job position with similar jobs until under normal operation the operator is doing 100% of a job. The manager must then consider the outside portion of those consolidated jobs and ensure that all the field positions are filled. This isn’t always as easy as consolidating console jobs which are all in the same room. The field can be geographically challenging and units can be miles apart. So added to the field operators workload is travel time.

The checklist may expose some of the assumptions about common management systems but it won’t identify all of the problems. It’s clear from this example that the training is going to be very different and that console operators will need extensive cross-training. Even if the written procedures are accurate, operators working as a close team have their own ways of implementing a procedure, and every shift tends to do it differently. We aren’t saying that this is a good practice only that this is a fact. Teamwork, in this case, is an impediment to cross-training. The danger of this impediment can be countered by preparatory meetings before procedures are carried out. This new organization would benefit from a more formal procedure with assigned jobs against job posts (descriptions).

After shuffling the deck a new organization may find that some tasks aren’t being done or that they are being done incorrectly. So many things in the past may have been communicated by face-to-face communication. Now, in the new structure, radio communication is relied on. Communication standards should be reviewed and the potential loss of the radio system should be thoughtfully considered. A generic checklist won’t work. This should serve as a caution against reliance on avoiding discussion while implementing an MOOC. Fortunately, a better guideline exists.

Perhaps a better way

The Contra Costa County (Calif.) Safety Council described requirements for OSHA covered processes to have a Management of Organizational Change program; with the main requirements in their ordinance cited in Chapter 7: Management of Change for Organizational Changes:

- 7.1 Forming a “Change Team” or “MOC Team;”

- 7.2 Defining the Existing Situation and Identifying Affected Areas;

- 7.3 Developing the Technical Basis for the Change;

- 7.4 Assessing the Impact of the Organizational Change on Safety and Health; and

- 7.5 Completing the Management of Change.

Most companies using the checklist can claim they have met the requirements of Sections 1, 4, and 5. The struggle begins with Sections 2 and 3 that are at the heart of the MOOC process. The U.K. Health and Safety Executive (HSE), the equivalent of OSHA, invested research into understanding MOOC from a best practice perspective. Part of this research involved studying how console operators deal with organization pressure:

Kecklund and Svenson (1997) asked control room operators to report on the strategies they use to maintain their performance. Operators stated they use the organization as a resource when coping with more demanding work situations such as arise during outages, by handing over tasks to others, postponing activities to the next shift, etc. They also judge that organizational factors, such as planning and shift change, had a bearing on misinterpretation errors. They also indicated lack of education, experience and knowledge as important contributor’s to misinterpretation errors, underlining the value of training. [1]

Reviewing known methodologies, the Executive concluded that what was required was a two-part analysis. The first step would be an investigation of the needs of the new organization compared to the old one. The next step would look at the capabilities required of each position. Working through selected fault trees will aid in evaluating these job positions.

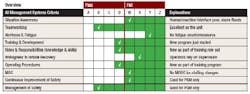

The cast of characters for this study is similar to a PHA team. A trained chairperson is needed to steer the discussion. The review starts with the management system overview using a ladder assessment to review organizational factors. The dotted line represents the boundary between acceptable and unacceptable practices (Table 1).

Table 2. Defining how your operators spend their time is a first step in establishing workflow. (Click to enlarge.)

There are 12 ladders in total; the following are considered to be key performance requirements of process control operators:

- Be able to follow the condition of the process, anticipate its behavior and hence, select an appropriate control strategy (i.e., have high ‘situation awareness’);

- Be in a fit state to monitor the process (i.e., be awake and attentive);

- Be willing to take action as and when necessary; and,

- Be able to take action, reliably and within the necessary time frame.

In addition, key team performance requirements are:

- Be able to collect and share critical information about the process and control actions; and,

- Be able to co-ordinate actions.

The review identifies many factors that influence the operator and team performance, including (in alphabetical order):

- Culture (e.g., openness, team spirit);

- Experience;

- Interactions with other activities (e.g., disturbances);

- Management of change;

- Number of staff;

- Procedure design;

- Process control technology;

- Roles and responsibilities;

- Training; and,

- Working hours (including shift pattern) [1].

In practice we have found it takes a couple of days to fully train a team. Once the team starts doing the management assessment we have found collecting evidence was the biggest time constraint and having experienced people in the room allowed for quick identification of issues. The expectation was that a site’s management system should be common for all units, but in practice we found differences. We also had to arrive at a compromise between an operator’s perception of a system and a supervisor’s view. However, once the ladder assessment was complete it was common for all the job posts being reviewed.

The physical assessment

The physical assessment tests the staffing arrangements against six‘’:

i) There should be continuous supervision of the process by skilled operators, i.e., operators should be able to gather information and intervene when required;

ii) Distractions such as answering phones, talking to people in the control room, administration tasks and nuisance alarms should be minimized to reduce the possibility of missing alarms;

iii) Additional information required for diagnosis and recovery should be accessible, correct and intelligible;

iv) Communication links between the control room and field should be reliable. For example, back-up communication hardware that is non-vulnerable to common cause failure should be provided where necessary. Preventive maintenance routines and regular operation of back-up equipment are examples of arrangements to assure reliability;

v) Staff required to assist in diagnosis and recovery should be available with sufficient time to attend when required;

vi) Operating staff should be allowed to concentrate on recovering the plant to a safe state. Therefore distractions should be avoided and necessary but time consuming tasks, such as summoning emergency services or communicating with site security, should be allocated to others. [1]

The assessment is in the form of specific questions, each requiring a yes/no answer (see Figure 1). The questions are arranged in eight trees. The choice of scenarios for assessment is critical and must consider the worst cases both in terms of consequence and of operator workload.

The physical assessment can be summarized from one of the HSE case studies:

The specification of scenarios in terms of the number, type and level of detailed description required, i.e., the need to identify scenarios which could result in incidents with major hazard potential. There should be no fixed rule on the number of scenarios that should or must be analyzed each plant or unit is different. It is recommended that scenarios representing the following are analyzed:

- Worst case scenarios requiring implementation of the off-site emergency plan;

- Incidents which could escalate without intervention to contain the problem on site;

- Lesser incidents requiring action to prevent the process becoming unsafe.

A site will also need to consider whether it is necessary to assess the scenarios at different times such as during the day and at night, during the week and at weekends, if staffing arrangements vary over these times.

It is necessary to define the circumstances of each scenario in sufficient detail. As a minimum:

- Define who is controlling the process and their starting locations;

- Define who is available to support the incident, and their starting locations:

- Define the parameters that determine the time available to the operations team for detection, diagnosis and recovery. [1]

In practice the physical assessment is only as good as the experience and knowledge of the assessment team. However, with the correct operations input the methodology can be invaluable, allowing a company to meet regulatory requirements and reduce the strain caused by MOC. We are not suggesting that this methodology eliminates the need for using the CMA checklist; we believe the CMA checklist makes the HSE methodology more complete. Two example forms are provided for the physical assessment (Table 1 and 2).

The combination of these two resources really allows a good grasp of the inside/outside job post and the process control operator or console operator post. Our experience has identified a shortfall in both methods and we suggest for the field post that additional study is required to address the issue we mentioned earlier, the time line.

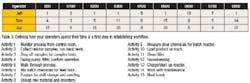

Most field operators have their own dedicated area, but sometimes that area can be made up of several units and can cover a wide physical area. What the other methodologies don’t do very well is consider these time issues and how a team works together. As a minimum, what is required is a time line identifying the who, where and when of each task for each person involved (Table 3).

Table 3. Defining how your operators spend their time is a first step in establishing workflow. (Click to enlarge.)

A better idea would be time-and-motion studies. This method should be favored for batch processes with lots of manual operations. Using this more advanced technique operator walk time or truck travel time from one location would be evaluated. It’s important to include minimum and maximum times and what other resources can be substituted in the event of a conflict. A conflict also may occur because of similar, simultaneous priorities from trains or equipment. In one example, consider the delay in production if the same truck bay is used for the final product and an intermediate — only one truck can be loaded at a time. Common mode failure should also be considered when evaluating the demands on a single roaming operator.

All of this does take time — a learning curve is involved; in practice once the process has been started a team can comfortably do a job position in a day. So if you’re looking at changing six job positions about ten days would be required, to collect common data such as scenarios and then run them through the existing and new job positions.

Passing the torch

The challenge faced by MOC teams is finding time to do these studies correctly and thoroughly. Until a methodology can be employed that balances the workload on existing workers, industry will continue to muddle through MOC — unless the regulators enforce a change. In the U.K., MOOC studies are done for every covered process. A government inspector can turn up at any time to audit a study or complete his own study.

The chemical industry often embraces good practices ahead of OSHA and EPA enforcement. Our studies demonstrate that problems do exist. Industry has evolved jobs haphazardly. We have arrived at position where wide variations in workloads exist between groups of operators, supervisors and managers. People aren’t being used to efficiently man jobs. We have determined that a company may have the right number of people but have them doing wrong things. They aren’t sharing workload and the burden falls on a few.

As an industry we are coming of age so to speak as our seasoned workers will begin to retire in the next five years. Unfortunately it isn’t just operators; it’s also maintenance, supervisors, engineers and managers. A company needs to really understand the impact of what is on the horizon as far as new versus old workers. It isn’t good enough to wait until the crisis is here; companies need to be preparing, planning and hiring workers now. There are other concerns unique to our time in history.

Think of it — all that corporate knowledge is about to be hitting the golf courses and beaches at the same time! Any attractive workers will be on the fast track to promotion and will be very interesting to other companies and competitors. This will eventually end in a price war for employees. We have seen it happen before but we may not have seen it on this scale.

All of this means change, change, and more change and it will benefit a company to have a good handle on MOOC. More than a century ago, the great scientist Louis Pasteur said, “Chance favors only the prepared mind.” By this, he could have meant that sudden flashes of insight don’ts just happen, but are the product of preparation.

To resolve both the MOC and MOOC problems the organization must be prepared for the changes it will inevitably have to experience. The first step, is understanding the problem, the second will be designing the right organization or right-sizing the organization and then having a technique to validate that proposed organization. In our industry we don’t get too many chances to do this, so I suggest we do it properly, which means safely, which also means cost effectively.

References

1. “Assessing the safety of staffing arrangements for process operations in the chemical and allied industries,” pp. 11, 17, iii and 175, Entec U.K. Ltd. for the Health and Safety Executive — Contract Research Report 348/2001 (2001).

Ian Nimmo is president and founder of User Centered Design Services, Anthem, Ariz., a firm that specializes in abnormal-situation management and other control issues. E-mail him at [email protected].