If you blinked at some point this summer, you may have missed the peak of the current business turnaround in the U.S. chemical industry. In its “Mid-Year Business of Chemistry Situation and Outlook,” the American Chemistry Council (ACC), Alexandria, Va., forecast that growth had accelerated during the first half of this year and that the industry would post a 4.5% growth rate in value of shipments for the year. However, there are signs that growth is already slowing down; ACC predicts a drop in rate to 3.8% in 2005. If the industry’;s traditional cyclical pattern holds, growth will continue to decelerate after that. However, slower growth certainly is better than no growth. It marks something of an accomplishment, given the frustrating cycle faced by the industry during the past three years when repeated forecasts of a turnaround never panned out.

Part of this growth is coming from stronger exports. While the U.S. chemical industry has been running a trade deficit since 2002 — and will again this year — the deficit is expected to shrink somewhat by the end of 2004 (Table 1; view it by clicking on the Download File button at end of the article). Based on U.S. Department of Commerce data through the middle of this year, ACC finds that chemical exports are up 17.4% overall, to nearly $53 billion. Imports are up, too, but only by 12.6%, to $56.3 billion.

Domestic trouble on the horizon

American plants now are benefiting from this worldwide expansion, but the long-term trends for U.S. producers are less upbeat, say a number of market forecasters. They worry about the disappearance of low domestic natural-gas prices, which for decades have fueled U.S. petrochemical production; higher petroleum prices worldwide, which will affect the economics of the chemical industry and favor countries with abundant petroleum supplies; and the continuing impact of China as a global manufacturing force.

Instead of its historic advantage in natural gas cost, the United States currently has the highest price in the world. Citing a variety of industry sources in its mid-year report, ACC says natural gas averaged $6.30 per million Btu in the United States, compared to $4.80 in Germany, $4.55 in China, and $1 or less in South America, Russia and the Middle East. Most industry sources view the current situation as a localized capacity crunch brought on by increased demand for natural gas for electricity production. But they also warn that natural gas prices are unlikely to return to their historic average of $2 to $4 per million Btu.

Manufacturers of automobiles, household appliances and the like have talked much in the past year about the “China price” for a component or subassembly. This is a shortcut way of saying, “I can source this product in China at a lower price. Can you match it?” Industry experts say the China price is starting to have an impact on chemical production as well. “Aspartame, the artificial sweetener, is a good example,” says Dilip Chandwani, a vice president at the market-research firm Kline & Co., Little Ferry, N.J. “It started as a single-source product from G.D. Searle [now part of Monsanto], then saw competition from a few other Western producers. Now there are a dozen places you can go to in China where it is available at a low price. The quality might not be there yet, but it is coming up rapidly,” he says.

Peterson’;s example also highlights a hidden part of the global chemical business — the “contained trade” of chemicals that are part of products imported into the United States. In government statistics about imports, these don’;t show up as imported chemicals; however, to the domestic producer whose customer base has moved abroad, they are the equivalent of imported competition.

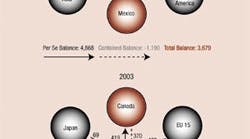

Peterson’;s firm is one of several that are now looking more closely at the distinctions between direct, or “per se,” trade in chemicals and “contained” trade. As Figure 1 indicates, the trends are not promising. “Our expectation that engineering resins would be less affected by contained trade was based partially on our belief that the U.S. trade balance in nondurable goods, which use commodity resins like polyethylene, has been hurt more than the balance in durable goods — things that last longer than a year,” he says. Comparing 1997 to 2003 shows that even in these premium materials, the U.S. trade situation is deteriorating. In commodity resins, it is already negative, with a total deficit (considering direct and contained trade) of -$1.9 billion in 2003. Petrochemicals, synthetic rubber and adhesives, which all run a direct deficit, look a lot worse when contained trade is included.

Regardless of whether U.S. chemical companies go abroad or not, they should be thinking about a global strategy,” he concludes. “The pace of innovation might have to speed up, or the company might simply decide to return more money to its shareholders.”